The ECGI blog is kindly supported by

When Corporate Climate Promises Don’t Match the Numbers: The 2025 ECGI Wallenberg Lecture

A review of the 2025 Wallenberg Lecture “Decarbonisation Commitments: Signals, Substance, or Spin?” delivered by Professor Marcin Kacperczyk (Imperial College London and ECGI), followed by commentary from Professor Estelle Cantillon (Université libre de Bruxelles).

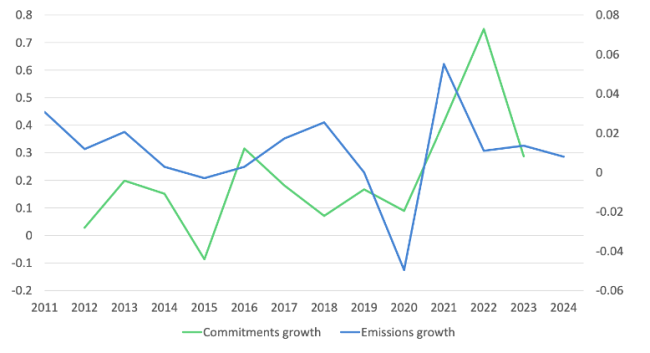

The 2025 ECGI Wallenberg Lecture by Marcin Kacperczyk (Imperial College London) confronted an uncomfortable paradox: as the number of corporate net-zero pledges has surged, global emissions have continued to rise. “If more and more companies are committing to decarbonisation, shouldn’t we be seeing the emissions curve bending down?” The data suggest otherwise.

The lecture examined what corporate climate commitments really represent and whether they deliver measurable progress. With the global climate agenda unsettled and financial intermediaries retreating from once-ambitious net-zero alliances, the analysis offered a reality check on how far voluntary corporate pledges have carried the decarbonisation effort—and where they have fallen short.

Setting the stage, Kacperczyk reminded the audience that climate change is no longer a matter of debate. The rapid rise in global temperatures can be explained almost entirely by human activity, according to the IPCC.

“..there is still this kind of notion that maybe this is about volcanoes, maybe this is about solar activity. I think this is really a myth — this is all about what humans do.”

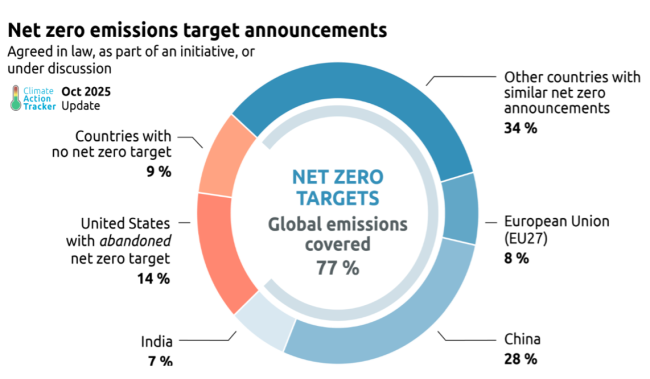

The policy response since the 2015 Paris Agreement has been to mobilise “coalitions of the willing.” Countries, sectors, and companies have lined up behind pledges to reach net-zero emissions. At the national level, roughly three-quarters of global emissions are now nominally covered by some form of commitment. But the United States’ withdrawal from the Paris framework earlier this year left a visible dent in that share—an early sign of how fragile global coordination can be.

Commitments at the firm level

The real question, however, lies beneath the country level. Decarbonisation cannot rest solely on governments; the real work happens “at the base,” within sectors and firms whose actions determine whether policy goals materialise. The focus turned to corporate commitments made through the two dominant frameworks: CDP (formerly the Carbon Disclosure Project) and the Science-Based Targets initiative (SBTi). Both allow firms to declare quantitative emissions-reduction targets aligned, in principle, with the Paris goals.

The data reveal an impressive mobilisation: more than 3 000 firms worldwide have now registered formal decarbonisation targets. Yet the depth and durability of those pledges vary sharply. About half of all corporate pledges have time horizons shorter than eight years, only 9 % extend to 2050, and just 12 % commit to full decarbonisation. Most aim for reductions of less than 50 % relative to their baseline year.

These patterns matter because the aggregate picture is sobering. Global data show that while corporate commitments have increased exponentially, emissions have also grown, producing a positive correlation of 0.32 between the two. That is the opposite of what one would expect. The finding is not causal, but it exposes a striking disconnect between corporate declarations and real-world outcomes.

Who commits—and why

But when you dig deeper, you find a selection effect behind the paradox. Companies with already low emissions are far more likely to make decarbonisation pledges. High-emitting firms, in contrast, tend to stay silent. As a result, even when low-emission firms deliver on their promises, the aggregate effect is overwhelmed by rising output elsewhere.

Corporate commitments follow a rational cost–benefit logic. Firms balance reputational and financial gains against the direct and indirect costs of reducing emissions. His new analysis suggested that credible pledges can slightly enhance firm value, whereas failure to meet them is financially punished. Joining initiatives such as the SBTi may signal responsibility and reduce financing costs, but it also exposes firms to reputational and economic risk—one reason many avoid binding targets altogether.

One behavioural pattern illustrates this caution. Many firms “backdate” their commitments—setting the baseline year for emissions reductions in the past, often at a peak level, to make future progress appear steeper. Emissions are typically highest in the chosen base year, confirming that companies select it strategically to “get a head start.”

Even among those that commit, most are lagging. About 72 % of firms are behind schedule relative to their pledged trajectories over the past decade, and 56 % remain off track even on a three-year measure. The average firm’s emissions-reduction rate is 5.8 percentage points lower than what its pledge would require. The reasons vary: firms with rapid sales growth or extensive supply-chain (“Scope 3”) emissions tend to fall furthest behind, suggesting that expanding businesses struggle to reconcile decarbonisation with performance targets. Longer-term pledges, by contrast, show smaller shortfalls, hinting that gradual pathways may be more realistic.

Financial pressures and governance

Kacperczyk then turned to the role of external governance—how banks and asset managers, through their own climate commitments, can influence borrowers and portfolio companies. Drawing on his earlier research, analysis of 22 global banks that joined the SBTi and committed to net-zero lending portfolios shows that after these commitments, high-emission borrowers experienced a measurable decline in credit availability, whereas clients of non-committed banks did not.

Borrowers responded as expected to tighter financing conditions: they reduced leverage, investment, and assets, while holding more cash to buffer against uncertainty. Yet the environmental effect was negligible. Companies treated the banks’ decarbonisation demands as a cost of doing business, not a call to change it. Rather than cutting emissions, they improved their “soft ESG” profile—issuing statements and policies that signalled concern but left operations largely unchanged.

Profitability even rose as firms reallocated resources to higher-margin activities, dropping projects that were less profitable but not necessarily more carbon-intensive. The outcome shows both the power and the limits of financial discipline: lending constraints can alter firm behaviour, but not necessarily in the intended direction.

The same coordination fragility now confronts asset-management initiatives. The Net-Zero Asset Managers Initiative (NZAMI), once representing over half of global assets under management, reached its peak with $61 trillion before major participants began to withdraw. By early 2025, operations were paused: “once the big players started moving out, everyone else felt like that doesn't give them much credibility.”

A sobering outlook

Even under the most optimistic assumptions, the world is on track to overshoot the Paris Agreement’s 1.5 °C goal. Climate Action Tracker data show that even if all existing pledges were fully realised, global temperatures are still likely to rise between 2 °C and 3 °C—and in parts of the northern hemisphere, closer to 5 °C or more. What is most unsettling is how quickly this reality is being normalised: policymakers now speak of a “two-to-three-degree world” as if it were inevitable.

Following the lecture, Professor Estelle Cantillon (Université libre de Bruxelles) highlighted a structural weakness behind many corporate climate pledges: the erosion of transparency. Market disclosure is not a side issue but the foundation of credible commitments. Without reliable, verified reporting on emissions, targets and trajectories lose meaning. Europe’s recent decision to narrow the scope and delay implementation of its Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive risks undoing years of progress on accountability—mirroring a similar rollback of disclosure rules in the United States. Voluntary reporting and estimated data, on which most carbon databases still rely, cannot fill that gap.

Cantillon also framed climate action as a coordination game. The more firms act, the greater the incentive for others to follow, creating self-reinforcing momentum. But that equilibrium is fragile: when leading actors retreat, collective confidence falters, as seen in the asset-management sector. Sustaining credible disclosure and coordinated action is therefore essential—not only for market integrity but for the legitimacy of the transition itself.

__________________________

The ECGI does not, consistent with its constitutional purpose, have a view or opinion. If you wish to respond to this article, you can submit a blog article or 'letter to the editor' by clicking here.