The ECGI blog is kindly supported by

Do corporate climate pledges actually clean up oil operations in Africa? Yes — mostly.

If you work around climate or human rights, you’ve probably rolled your eyes at glossy corporate “net-zero” promises. Who hasn’t? Too often, commitments feel like PR varnish—long on slogans, short on substance. That’s why our new paper on the World Bank’s “Zero Routine Flaring by 2030” (ZRF) pledge is worth your time. It focuses on the African oil and gas sector, where local environmental standards are weaker, monitoring is harder, and the temptation to greenwash is strong. The headline: companies that sign ZRF do, on average, cut flaring—and they do it mainly by improving operations, not by quietly dumping dirty assets onto less scrupulous operators. That’s a big deal.

First, the what and why. Gas flaring—the controlled burning of natural gas during oil extraction—releases CO₂ and harmful local pollutants. It’s an old habit that persists because capturing and transporting gas can be expensive, especially where pipelines and demand are thin. The ZRF commitment is simple in theory: no routine flaring by 2030, with progress disclosed at the company level. That consolidated reporting matters. It effectively imposes a firm-wide “price” on flaring (via reputational and financing consequences), regardless of where the barrels are pumped. If that theory works, companies should target the cheapest reductions first—often in places like Africa where the baseline is bad and improvements are relatively low-cost.

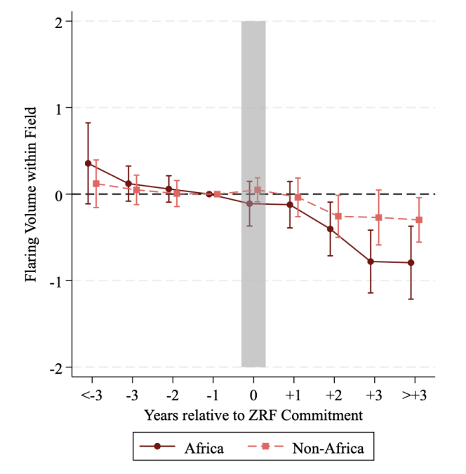

So, do signatories follow through? Using global World Bank flaring data, we find signers cut reported flaring by about 37% within three years. Crucially, the effect is far stronger in Africa: about 54% lower after three years versus 24% elsewhere.

That pattern is exactly what we’d expect if a firm-wide commitment bites hardest where local rules don’t. In other words, these aren’t just pledges that sit on websites—they appear to change behavior on the ground, especially where it’s most needed.

But is it “real” change or creative accounting? The classic critique is that companies meet green goals by selling off their dirtiest assets to uncommitted buyers—so the pollution doesn’t go away, it just changes owners. We dig into this by assembling higher-resolution block-level data for North and West Africa and marrying it with satellite readings of flares (Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) Nightfire) and methane concentrations (Sentinel-5P). Two checks matter here:

- Operational improvements: For oil blocks that firms keep operating, flaring falls ~41% over three years after commitment. That’s the bulk of the emissions story.

- Venting substitution: If firms were gaming the numbers by turning off visible flares and simply venting methane (much worse for the climate), we’d expect methane spikes. The paper doesn’t find that. Methane levels at committed blocks look similar—or if anything, slightly lower—than uncommitted peers in 2019–2023. That’s a key integrity check.

What about the asset shuffling we read about in the press? It happens, but it’s not the main story. After committing, firms are less likely to win new block awards (the award probability dips by ~15% a few years post-commitment), and there are sales to uncommitted buyers (figures in the paper show 11 such divestitures in the sample). And yes, this reallocation hurts:

- Blocks awarded to uncommitted firms flare about 28% more than if they’d gone to committed firms.

- Blocks divested from committed to uncommitted operators see a 153% increase in flaring within three years.

Those are ugly increases. But they’re relatively rare compared to the number of blocks companies keep and fix. In short: leakage exists, but it doesn’t dominate.

Net impact: still positive—and large. When we stack up the three channels (improvements on blocks firms keep, forgone awards, and divestitures), they estimate an annual net reduction of ~58 million metric tons CO₂-equivalent in Africa after commitments. That’s roughly the yearly emissions of 12.6 million passenger cars, or 0.15% of global CO₂ in 2022—not world-saving, but far from trivial for one operational practice in one region.

Why this matters for NGOs and policymakers. A few takeaways jump out:

- Firm-wide metrics can beat fragmented regulation. Because ZRF progress is tracked at the consolidated company level, pressure from investors, lenders, and civil society sets a de facto global price on flaring for the company—no matter where it drills. That uniform pressure is why the biggest improvements show up exactly where local standards are weakest.

- Monitoring tech is your ally. Satellite-based flaring and methane data make it much harder to fudge numbers. That visibility is likely part of why the study doesn’t detect a pivot to venting. NGOs should keep championing public, high-resolution remote sensing and insist companies reconcile their internal numbers to independent datasets.

- Guardrails against leakage still matter. The award and divestiture results are a caution flag. Even if asset shuffling is a minority of cases now, it causes real damage when it happens. Campaigns and policy should target the market for assets—for instance, transparency on lifecycle emissions at the asset level, stronger buyer commitments, and lender covenants that travel with the asset.

- Be realistic about causality—but insistent about accountability. We are careful and don’t claim the commitment causes the improvements, only that actions taken by firms that commit line up with their disclosures. For our purposes, that distinction matters less than the consistency: if a company pledges and then its flaring falls—without a methane spike—call that progress, then push for more.

The bottom line (and it’s a bit refreshing): In Africa’s oil sector, ZRF signatories are, on average, walking the talk. They are cutting routine flaring in the assets they keep, and satellites don’t show a covert switch to venting. While some pollution leaks back through awards and sales to uncommitted firms, those channels don’t wipe out the gains. Net effect: tens of millions of tons of CO₂-equivalent emissions avoided each year on the continent. That’s not corporate sainthood—far from it. But it’s evidence that focused, measurable commitments, backed by firm-wide accountability and independent monitoring, can move the needle where government rules are patchy.

Here’s the challenge for NGOs: don’t let up. Use this proof to demand tighter timelines, asset-level transparency, and buyer-side commitments so the 2030 finish line doesn’t trigger a last-minute dumping spree. Celebrate the real reductions, expose the leakage, and keep turning reputational pressure into operational change. If we do, pledges like ZRF won’t just be slogans—they’ll be tools that actually cut pollution, in the places that need it most.

-----------

Samuel Chang is a fourth-year Ph.D. candidate in accounting and Ernest R. Wish Research Fellow at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business.

-----------

This blog is based on a paper presented at the First Annual Corporate Governance Academic Forum at the University of Toronto. Visit the event page to explore more conference-related blogs.

The ECGI does not, consistent with its constitutional purpose, have a view or opinion. If you wish to respond to this article, you can submit a blog article or 'letter to the editor' by clicking here.