The ECGI blog is kindly supported by

Costly Sabotage: The Dark Side of Improved Risk-Sharing

Sabotage as a Means of Success

It’s a tale as old as time: outperforming the competition is often less about being at your best—and more about making sure your competitors aren’t at their best. Want to take home the Gold medal in figure skating at the Olympics? Tonya Harding has a strategy for that. Want to win an election? Might be a good time to air your opponent’s dirty laundry on live television. Want to dominate your soccer league? Just ask Bayern Munich for tips on draining your rivals’ talent pool year after year.

As far back as The Odyssey, we have Penelope’s many suitors, all vying for her hand and, with it, the kingship of Ithaca. So, of course they all try their best to win Penelope’s affection through demonstrations of personal virtue and valor, right? Wrong. They conspire, stall, and sabotage one another. They drink each other under the table. They whisper gossip. They maneuver to discredit rivals rather than distinguish themselves. The objective isn’t to showcase their best—it’s to be the last one standing. In this ancient, zero-sum game of relative status, advancement comes more readily from peer degradation than from self-improvement.

At the heart of all these examples is a simple structural feature: the primacy of relative performance. It’s not just how well you skate; did you skate better or worse than the competition? It’s not just how many votes you get; did you earn more or fewer votes than your opponent? When the metric that determines success is comparative rather than absolute, sabotage becomes rationally self-serving. After all, it’s often easier to trip others than sprint faster.

That logic may seem confined to athletic competitions, electoral politics and Greek tragedy. But it plays out every day at the highest levels of corporate America—quietly driven by an increasingly-dominant feature of executive pay packages: relative performance evaluation (“RPE”).

Executive Pay Based on Relative Performance Evaluation

Over the past two decades, usage of RPE in CEO pay plans has nearly tripled, and is now used by the majority of large publicly-traded American companies. It’s one of those ideas that, at first blush, just makes sense. Why not tie executive pay to how a CEO’s company does relative to its peers? After all, this should filter out luck (whether good or bad), reward real skill and productive hard work and generally push executives to strive for their firm’s best possible performance—right?

Well, sort of. To be sure, RPE does help with risk-sharing. You probably don’t want to reward your CEO for a booming macro economy, and you don’t want to punish them for a recession either. Evaluating firm performance on a relative basis, comparing against “peers” that are similarly exposed to these economic swings, can be a highly effective way to cut through the noise and avoid “pay for luck.”

But there’s a catch. Working smart/hard to boost your firm’s performance is one way to improve your relative standing. But taking steps to undermine your peers and harm their performance works too. And here’s the kicker: sabotaging a peer can pay off even if it harms your own firm—so long as the harmed peer suffers more than your own firm does, you still win (and receive higher compensation).

But how does this play out in a world of strategic alliances, robust governance structures, litigious counterparties and powerful common-owning blockholders? Enter strategic talent poaching.

Corporate Sabotage Gets Personnel

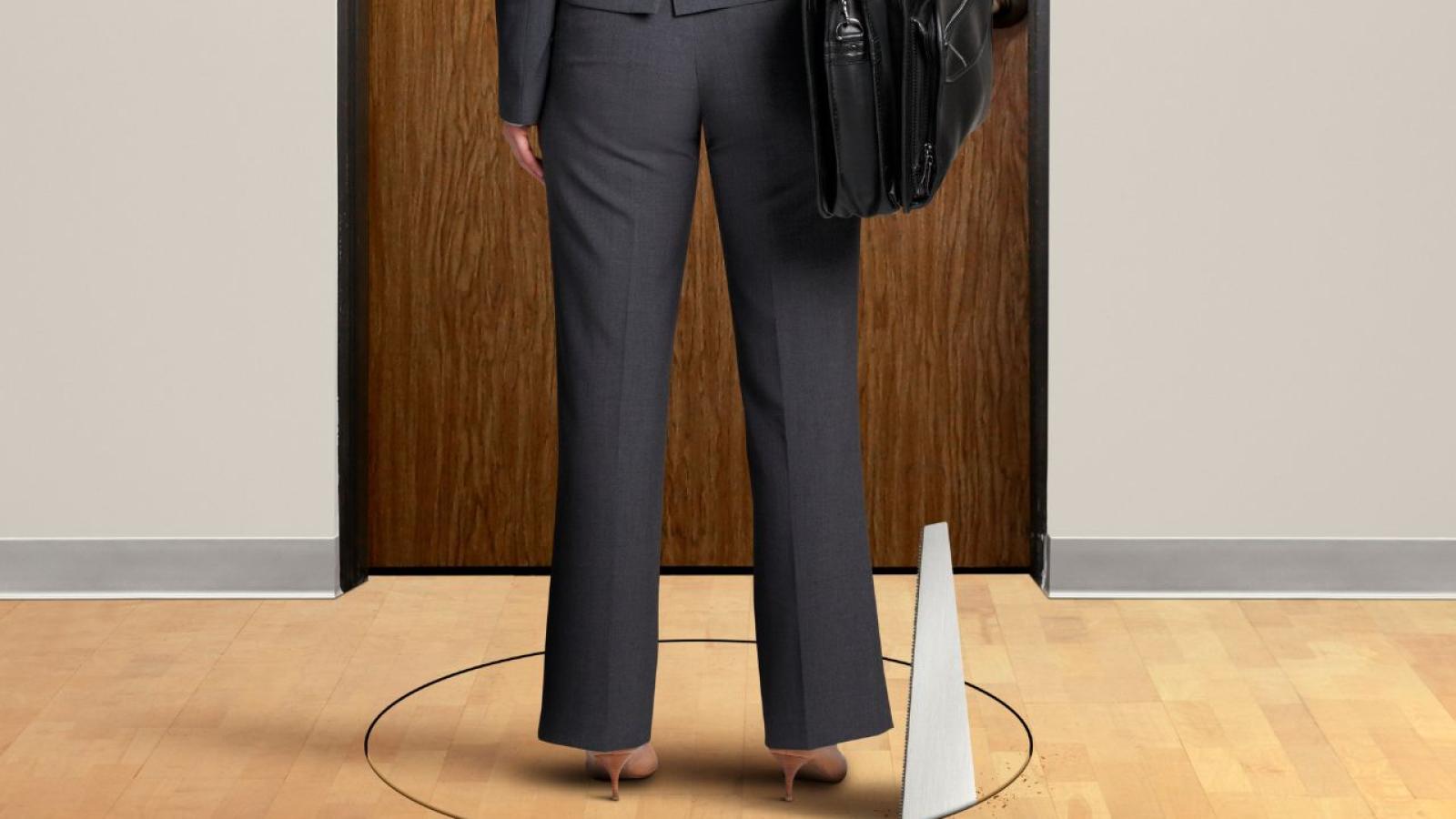

Suppose you’re a CEO with a lot of incentive compensation tied to relative performance metrics. If you can drag down your peers’ performance—even marginally—this can be just as valuable as lifting your own performance. And what better way to slow down a rival than by siphoning off its “most crucial asset” by poaching away their most skilled and hardest-to-replace workers?

This is exactly the sabotage strategy documented in a new paper by Bloomfield, Bourveau, Lin, She, and Zhu. Firms poach significantly more employees—especially highly skilled, long-tenured ones—from the peer companies against whom their relative performance is benchmarked. Notably, this isn’t a general industry trend; it’s a targeted strategy that ramps up immediately after a rival is added to an RPE peer group. And it’s not reciprocal: the rival doesn't poach back, suggesting this is a one-sided, incentive-driven strategy—not a reflection of economic similarity or shared talent needs, but a peer-harming sabotage tactic.

In turn, the targeted peers find that labor talent becomes a more expensive input into their production process, as this external poaching pressure effectively means the RPE peers are engaged in more intense competition for their own employees.

What This Means for Corporate Governance

The findings raise thorny questions for corporate boards. If RPE incentivizes executives to undermine rivals’ performance—even potentially at the expense of their own—should we still treat it as a best practice in pay design? More fundamentally, how do we best align pay-for-performance incentives with value creation rather than value destruction?

Traditional views of competition assume that firms will innovate, cut costs, and improve quality to outperform their peers. But this new branch of research points to a darker possibility: firms might instead engage in quiet acts of sabotage—aggressive talent raids, predatory pricing, or even negative disclosures—if doing so moves the needle on their pay.

For governance practitioners, the message is clear: RPE’s risk-sharing benefits don’t come for free. Using rivals as RPE peers imposes costs on them—and strategic temptations for you. As companies rethink executive pay in an era of heightened scrutiny and stakeholder accountability, this paper reminds us that incentives work. Sometimes a little too well. And like the suitors in Odysseus’s halls, today’s CEOs may find that getting ahead doesn’t always require rising above. Sometimes, you just need your rivals to fall.

_______________

Matthew J. Bloomfield is an Assistant Professor of Accounting at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania

Thomas Bourveau is an Associate Professor of Business at Columbia Business School, and an ECGI Research Member

Xuanpu Lin is a Research Postgraduate Student in Accounting at HKU Business School, University of Hong Kong.

Guoman She is an Associate Professor of Accounting at National University of Singapore.

Haoran Zhu is an Assistant Professor at the College of Business, Southern University of Science and Technology.

The ECGI does not, consistent with its constitutional purpose, have a view or opinion. If you wish to respond to this article, you can submit a blog article or 'letter to the editor' by clicking here.