The ECGI blog is kindly supported by

When Market Frictions Reduce, Carbon Performance Improves: The Role of Competition

The problem: Climate ambition outpaces policy incentives

Modern economies rely on firms to produce goods and services, yet much of the climate damage associated with this production is not reflected in firms’ private costs. As a result, companies can emit greenhouse gases at little or no direct cost, while society bears the consequences. A central challenge of climate policy is therefore to design frameworks that limit firms’ ability to exploit these negative externalities.

So far, no comprehensive policy approach has succeeded in aligning firms’ incentives with global climate objectives. Despite increasingly ambitious targets, existing policy frameworks remain insufficient to deliver emissions reductions consistent with the Paris Agreement. According to the Climate Action Tracker, global warming under current climate policies is projected to reach around 2.6◦C by 2100, well above the objective of limiting warming to 1.5◦C.

This misalignment is clearly visible in current carbon pricing regimes. Although carbon pricing is designed to encourage firms to take climate costs into account, it remains uneven and incomplete. As reported by the World Bank, direct carbon pricing covers only about 28% of global greenhouse gas emissions, resulting in a global emissions-weighted average carbon price of around USD 5 per ton of CO2, far below Paris-consistent benchmarks of roughly USD 50–100 per ton by 2030.

A key question is therefore whether other market forces can help reduce firms’ emissions when formal climate policy falls short. In our recent paper, we examine whether product-market competition affects firms’ incentives to reduce carbon emission intensities. Exploiting large and unexpected reductions in U.S. import tariffs as plausibly exogenous shocks to competition, we provide causal evidence on how competitive pressure shapes firms’ carbon efficiency.

Competition and carbon emission intensities: Evidence from tariff cuts

Competition is widely recognized as a powerful force influencing how firms operate. A large body of research shows that competitive pressure influences firms’ performance (Bloom and Van Reenen, 2007), corporate governance (Giroud and Mueller, 2011), investments (Jiang et al., 2015), and broader corporate social responsibility activities (Flammer, 2015). What remains much less clear is whether similar competitive forces also affect firms’ carbon emissions. Reducing emissions often requires costly, long-term investments, making it unclear whether stronger competition encourages such efforts or instead discourages them by squeezing profit margins.

To shed light on this question, we focus on large and unexpected reductions in U.S. import tariffs, which increase competitive pressure in affected industries. Lower tariffs make foreign goods cheaper relative to domestic ones and intensify competition in U.S. markets, without being driven by firms’ environmental choices. In practical terms, tariff reductions increase competition—or at least the threat of competition— facilitating the entry and expansion of foreign firms into domestic markets.

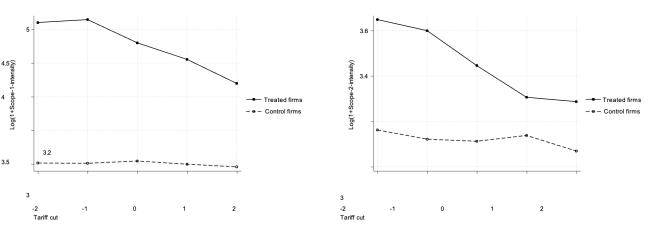

In this regard, our results show a clear and economically meaningful effect for firms operating in industries exposed to tariff reductions. Figure 1 illustrates the evolution of Scope 1 and Scope 2 emission intensities around large, unexpected tariff cuts. Prior to the tariff reduction, treated and control firms exhibit similar trends. Following the tariff cut, firms in exposed industries experience a pronounced and persistent decline in emission intensities, while firms in unaffected industries show no comparable change. This divergence suggests that increased competitive pressure, rather than common time trends, drives the observed reduction in emissions intensity.

Figure 1: Evolution of Scope 1 and Scope 2 emission intensities around tariff cuts

Notes: This figure shows the evolution of firms’ Scope 1 and Scope 2 carbon emission intensities around large and unexpected tariff reductions (tariff cuts). Emission intensities are measured as absolute emissions relative to revenue and transformed using the natural logarithm. The solid line represents firms operating in industries exposed to tariff reductions (treated firms), while the dashed line represents firms in unaffected industries (control firms). The horizontal axis indicates years relative to the tariff reduction, with t = 0 denoting the year in which the tariff cut occurs.

To quantify these patterns more precisely, we turn to the regression analyses that isolate the effect of in-creased competition. On average, firms facing stronger competition reduce emission intensities from their own production processes (Scope 1) by around 20–25 percent, and emissions from purchased energy such as electricity and heat (Scope 2) by about 10–15 percent. These effects materialize gradually over a three-year window, spanning the year before, the year of, and the year after the tariff reduction.

Importantly, the reduction in emission intensity does not come at the cost of higher absolute emissions. We find no evidence that firms exposed to tariff reductions increase their total emissions or simply shift production across firms or industries. Instead, the results point to genuine efficiency gains, with firms producing the same or greater output with lower emissions.

Because tariff reductions affect entire industries, we carefully test the robustness of these findings using alternative comparison groups, empirical specifications, and emissions data sources. The results remain stable across these checks and persist when emissions data from alternative sources, such as the London Stock Exchange Group (LSEG) and the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP), are used instead of Trucost.

Why tariff-induced competition can support decarbonization

The mechanism behind these results lies in how firms respond when competitive pressure intensifies. Firms with relatively low emission intensities tend to increase investment and environmental spending, pursuing deeper operational improvements and efficiency gains. Higher-emission firms are more likely to adopt visible environmental measures and reorganize their financing and asset structures. In both cases, competitive pressure influences incentives to protect competitiveness and reputation as scrutiny from customers, investors, and other stakeholders intensifies.

More broadly, tariff-induced competition changes firms’ incentives through channels that carbon policy and pricing currently struggle to activate. By exposing firms to stronger competitive pressure, trade liberalization can accelerate the adoption of more efficient production processes.

These findings do not imply that competition can substitute for climate policy. Carbon pricing and regulation remain essential to internalize the climate externality. However, our evidence shows that well-functioning, competitive markets can meaningfully complement climate policy by strengthening firms’ incentives to decarbonize. Even in environments where carbon prices remain low, uneven, or incomplete.

-----------------------------------

Manuel C. Kathan is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Chair of Climate Finance and at the Centre for Climate Resilience at the University of Augsburg.

Raphaela Roeder is a Research Associate at the Chair of Climate Finance and at the Centre for Climate Resilience at the University of Augsburg.

Sebastian Utz is a Professor of Climate Finance at the Chair of Climate Finance and at the Centre for Climate Resilience at the University of Augsburg.

Martin Nerlinger is an Assistant Professor at the School of Finance at the University of St.Gallen, and a Faculty Member at the Swiss Finance Institute.

This blog is on the paper presented at the 6th Annual RCF-ECGI Corporate Finance and Governance Conference, held in a hybrid format online and in Hoboken, New Jersey, on 13 and 14 December 2025. Visit the event page to explore more conference-related blogs.

The ECGI does not, consistent with its constitutional purpose, have a view or opinion. If you wish to respond to this article, you can submit a blog article or 'letter to the editor' by clicking here.