The ECGI blog is kindly supported by

The biodiversity promise of carbon markets looks weaker than advertised

Voluntary carbon markets have grown up fast. Corporate net-zero pledges, investor appetite for nature-based assets and increasingly sophisticated certification regimes have channelled billions of dollars into projects that promise to offset emissions while doing good for nature. Among the most frequently advertised benefits is biodiversity protection. Carbon credits backed by forests, wetlands or grasslands are routinely marketed as delivering a double dividend: climate mitigation and ecological conservation.

That promise is attractive. But it is also largely untested at scale.

In our research, we ask a simple question with uncomfortable implications for the market: do voluntary carbon offset projects actually improve biodiversity outcomes? Using global data rather than case studies or project narratives, we find little evidence that they do—and some indication that human pressure on ecosystems may in fact increase after projects begin.

Our analysis is the first systematic, global assessment of biodiversity impacts associated with voluntary carbon market projects. We compile a geocoded dataset of nature-based offset projects launched between 2000 and 2023 and link their boundaries to high-resolution, satellite-derived ecological indicators. Using event-study designs, we compare ecological trends inside project areas before and after implementation with those in carefully matched control locations.

To measure biodiversity-relevant outcomes, we focus on the Human Influence Index (HII)—a widely used composite indicator that captures land-use change, infrastructure, accessibility and population density. Because habitat loss and degradation are the leading drivers of global biodiversity decline, changes in HII provide a meaningful signal of ecological pressure, even when species-level data are unavailable.

The headline result is revelatory. Across the global sample, we find no statistically significant reduction in human pressure following project implementation. Instead, project areas experience an average 3.7 per cent increase in HII after offsets begin. In other words, anthropogenic disturbance tends to rise, not fall, within the boundaries of voluntary carbon projects.

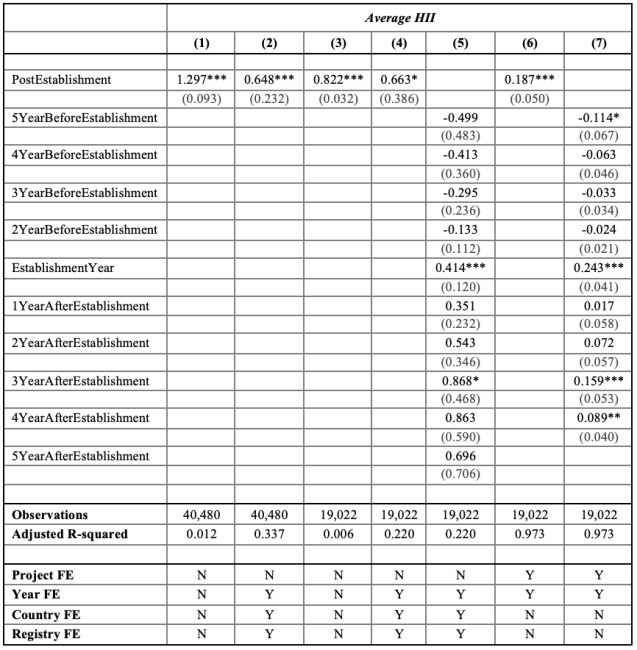

Table 1. Effects of Carbon Offset Project Implementation on Habitat Condition.

This table reports the effects of carbon offset projects on the Human Influence Index (HII) over the period 2000 - 2020. The dependent variable in all specifications is the average HII, computed for each project through zonal analysis of gridded HII values within project boundaries. Columns (1)–(2) present results for the full sample, while Columns (3)–(7) restrict the analysis to a balanced panel spanning five years before and after project establishment. In Columns (1)–(4) and (6), the key regressor is PostEstablishment, an indicator equal to one for years following project initiation. Columns (5) and (7) include a set of time-period dummy variables capturing relative years around establishment. Standard errors are clustered at the project level. ***, **, and * denote significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

This does not mean that individual projects never deliver ecological gains. Some almost certainly do. But the market as a whole does not display the systematic biodiversity improvements that its marketing often implies.

These findings challenge a core assumption embedded in many carbon-market narratives: that carbon-rich ecosystems are also biodiversity-rich, and that protecting one automatically protects the other. While this alignment can hold in particular contexts, our evidence suggests it fails as a general rule.

Much of the existing evidence supporting carbon-biodiversity “win-wins” comes from small-sample case studies or theoretical arguments. By contrast, our large-scale empirical analysis shows that the relationship between carbon storage and biodiversity outcomes is neither automatic nor predictable. In some cases, project designs aimed at maximising carbon—such as monoculture plantations, intensive fire suppression or land enclosure—may actively conflict with ecological complexity and resilience.

The implications extend beyond academic debates. As biodiversity finance grows alongside carbon markets, investors, buyers and regulators face a growing verification problem. Biodiversity safeguards are increasingly referenced in standards and guidelines, but independent, data-driven validation remains rare.

Our study demonstrates that scalable tools already exist. Satellite-based indicators, geospatial matching and econometric methods can be combined to evaluate biodiversity outcomes globally and consistently. This matters because reliance on project documentation or self-reported narratives is unlikely to withstand increasing scrutiny.

For credit buyers and asset managers, weak or negative biodiversity outcomes translate into unpriced ecological and credibility risks. Companies that rely on offsets to meet climate commitments may face reputational, legal or regulatory exposure if co-benefit claims cannot be substantiated. Premium pricing based on biodiversity narratives is particularly vulnerable.

These risks are becoming more salient as regulatory oversight tightens. In the US, the Securities and Exchange Commission has increased its focus on climate-related disclosures and the use of offsets. At the same time, guidance from the Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market and the Voluntary Carbon Market Integrity Initiative explicitly references biodiversity safeguards. In Europe, the European Union is advancing legislation on environmental claims and substantiation. Carbon accounting alone will no longer be enough.

For investors engaged in stewardship and active ownership, the message is equally clear. Engagement with companies that rely on offsets should focus not only on carbon integrity but also on whether biodiversity claims are supported by independent, spatially explicit evidence. Asking tougher questions about co-benefits may improve transparency—and, ultimately, market credibility.

Voluntary carbon markets are unlikely to disappear. But if they are to mature, their claims need to be tested with the same rigour applied to financial performance. Biodiversity cannot remain a marketing add-on. Our findings suggest that, at present, it is more promise than proof.

__________________

Zoey Yiyuan Zhou is an Assistant Professor of Climate at Columbia Climate School.

Douglas Almond is a Professor of International and Public Affairs and Economics at Columbia University, and an NBER Research Associate.

This blog is based on Zhou, Z. Y., & Almond, D. (2025). Biodiversity Co-Benefits in Carbon Markets? Evidence from Voluntary Offset Projects. Review of Finance, https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfaf066

The ECGI does not, consistent with its constitutional purpose, have a view or opinion. If you wish to respond to this article, you can submit a blog article or 'letter to the editor' by clicking here.