The ECGI blog is kindly supported by

The Labor Market Impact of Shareholder Power

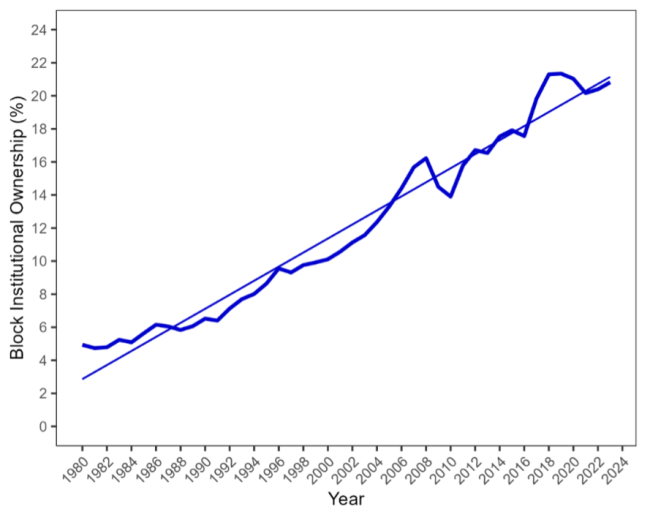

Economists and policymakers have sought to answer the question of what explains the stagnation of labor in the United States over the past few decades. In my paper entitled “The Labor Market Impact of Shareholder Power: Worker-Level Evidence” with Antonio Falato, Daniel Gallego, and Till von Wachter, we put forward an explanation that hasn’t been looked at in a systematic way—the rise of shareholder power. Figure 1 shows that over the last few decades, shareholder power, as measured by the average total block institutional ownership of public firms, has on average increased fourfold. Our shareholder power story posits that as the firm’s ownership becomes more concentrated, shareholders influence firms’ decisions more and can maximize shareholder value more effectively. There are two plausible ways this can happen. First, powerful shareholders can use their influence to shift resources away from workers and towards shareholders. Second, they could monitor firm managers and discourage them from hiring a large work force or paying higher wages to employees. In both cases, the result would be improved shareholder returns at the expense of worse worker outcomes, such as earnings.

Figure 1 - Trends in total block institutional ownership, 1980-2024

Note: Total block institutional ownership is defined as the total percentage share of equity owned by all institutional investors that own at least 5% of the shares of a given firm as filed through Form 13F. The average total block ownership is calculated excluding firms in the agriculture, financial, utilities, and public administration sectors. The Straight line indicates the linear time trend. Source: Thomson Reuters/WRDS 13F filings data.

To explore this hypothesis, we use confidential US Census data and analyze how increases in institutional ownership concentration affect establishment-level workforces (an “establishment” refers to a single physical location where a business conducts its operations, such as a store, factory, or office) and individual-level labor earnings. This idea is tested by comparing a “treated” group, consisting of establishments or workers that experience an increase in total block institutional ownership of more than five percentage points, with a “control” group comprised of establishments or workers that also experience an increase in overall institutional ownership of more than five percentage points – but not total block institutional ownership. This approach rules out any effects brought by increased institutional ownership level and instead isolates the effects of increased institutional ownership concentration—hence “power.” Finally, we examine how shareholder power affects workers of different earnings ranks.

Our results show that establishment-level employment and payroll trended similarly between the treated and control groups prior to the increases in institutional ownership concentration. However, after the increase in ownership concentration, treated establishments experience losses by about 2% for both employment and payroll relative to control establishments. (Our companion paper describes these establishment-level results in detail.)

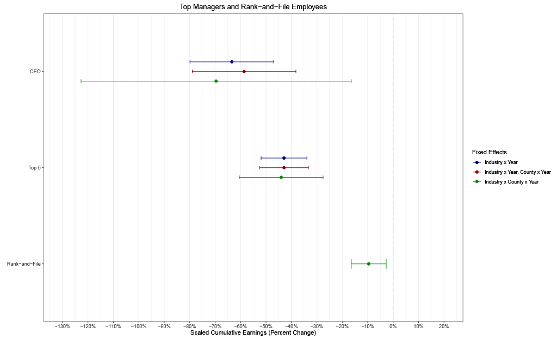

In terms of earnings losses at the individual worker-level, we find that high-skilled workers and top managers are affected the most. Figure 2 shows the effect of institutional ownership concentration on the earnings of treated firms’ employees segmented into three categories: CEOs (the highest earners of each firm), the five highest earners (including CEOs), and the rest of the workers (called rank-and-file). The results show that the CEOs of treated firms lose 63% of their pre-event annual earnings over the six post-event years relative to CEOs of control firms. The five highest earners (including the CEOs) of treated firms experience a 43% reduction in earnings, on average. In comparison, rank-and-file employees only experience a reduction of 10% between their post- and pre-event annual earnings. One explanation for this result is that institutional investors with concentrated ownership may view cutting pay of highly paid employees as an effective way to reduce costs and boost shareholder value.

Figure 1 - Worker-level analysis of institutional ownership effects on scaled cumulative earnings

Note: Scaled cumulative earnings is defined as the sum of a given worker’s labor earnings from the first six years following treatment, scaled by the average annual earnings of the workers one to five years before treatment. The markers on the bold lines in the figure show point estimates, and the lines 95% confidence intervals based on standard errors adjusted for sample clustering at the firm level. Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Thomson Reuters 13F filings data.

Furthermore, the negative effects on employment and earnings are most pronounced for institutions with control motives, such as “dedicated” and “activist” institutions which take a more active role in influencing a company’s management and/or strategy. Conversely, for firms with institutions that do not play an active role, such as passive index funds, they do not experience large, negative effects on their employees’ outcomes. This supports the mechanism where institutional shareholders influence a company’s employee outcomes by leveraging their ownership concentration.

Expectedly, rising shareholder power seems to also directly increase shareholder value as measured by stock returns, excess of the broad stock market index. At the same time, labor productivity experiences a short-term negative effect, but virtually no long run effect. This finding indicates that shareholder power has a reallocative impact where the cuts in employment and wages are used to shift the value away from the workers and towards shareholders without boosting productivity.

Overall, our research provides evidence that the rise in shareholder power, as measured by institutional ownership concentration is a plausible explanation for the stagnating US labor market. With concentrated ownership constituting close to 40% of the overall ownership by institutional investors as of 2024, these findings are important to understanding the labor market outcome of workers in an economic environment in which institutions play an important role.

…………………………

I thank Roger Chen for excellent research assistant for this article.

________

Hyunseob Kim is a Senior Economist and Economic Advisor in the Economic Research Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago.

________

This blog is based on a paper presented at the First Annual Corporate Governance Academic Forum at the University of Toronto. Visit the event page to explore more conference-related blogs.

The ECGI does not, consistent with its constitutional purpose, have a view or opinion. If you wish to respond to this article, you can submit a blog article or 'letter to the editor' by clicking here.