The ECGI blog is kindly supported by

Can Shareholder Engagement Drive Meaningful Corporate Climate Action?

Large asset managers like BlackRock hold stakes in thousands of companies worldwide, most through index-tracking funds that they cannot easily sell. That makes exit an ineffective option for influencing corporate behaviour. Engagement, in the form of direct dialogue with companies, becomes the main tool. A new study reveals how this tool works in practice and what it achieves. The results show measurable gains in climate commitments, disclosure, and operational emissions, although the changes are more incremental than transformational.

The focus is on a form of intervention that is distinctive in the world of asset management: direct, private dialogue between an investor and the companies it holds. The study draws on proprietary records from 2020 to 2023, covering nearly 6,000 climate risk engagements worldwide. These records were linked to firm-level data on greenhouse gas emissions, exposure to climate regulation, climate-related incidents, disclosure practices, and voting patterns. Regression models were applied to identify which companies were targeted, and a difference-in-differences approach was used to measure changes after engagement. This design helps isolate engagement effects from other factors, providing stronger evidence of causality rather than simple correlation.

The targeting pattern is clear. Engagement is concentrated in high-emitting sectors such as Utilities, Petroleum and Natural Gas, and Banking, industries where the risks of the energy transition are substantial. At the company level, the probability of engagement increases with absolute Scope 1 and 2 emissions, regulatory exposure to climate policy, and the number of recorded climate-related incidents. Emissions intensity, meaning emissions per unit of sales, does not matter. Firm ownership structures or governance features also do not predict targeting. These factors do not explain engagement on other topics such as social or governance issues, which underlines that climate targeting is deliberate.

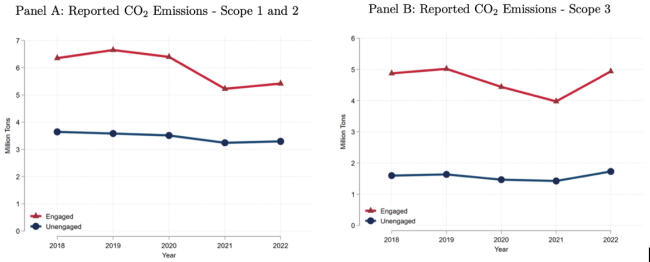

Evolution of Carbon Emissions for Firms Targeted by Climate Risk Engagement and Control Firms

The changes that follow are tangible, if measured. Firms engaged on climate are more likely to adopt a science-based target through the Science Based Targets initiative, with the probability rising by 4.4 percentage points over two years compared to a baseline commitment rate of 8 percent. This result is statistically significant and concentrated among high-emission, high-risk firms. Companies that had not previously responded to the Carbon Disclosure Project questionnaire are more than 11 percentage points more likely to begin disclosing after engagement.

The impact on emissions is visible but modest. Targeted companies reduce Scope 1 and 2 emissions by an average of 7.5 percent per year in the two years after engagement, relative to comparable firms. This reduction is statistically significant, but there is no significant change in Scope 3 emissions. BlackRock’s position is that Scope 3 will be prioritised once regulatory frameworks mature, framing this as a sequencing strategy rather than avoidance. Still, the absence of progress on Scope 3, which often makes up the bulk of a company’s carbon footprint, highlights a structural limitation of this model.

Voting behaviour offers a window into BlackRock’s strategy. At firms it is engaging on climate, it is more likely to support management in director elections, signalling a preference for cooperation over confrontation. It is also less likely to support climate-related shareholder proposals at these same firms, possibly to avoid conflicting with objectives pursued through private dialogue. The study finds no evidence that engagement leads to divestment decisions. The pattern overall suggests a conscious choice to maintain access and influence, even at the cost of appearing less aggressive in public votes.

Overall, the study finds that climate risk engagements lead to concrete shifts in company behaviour. Targeted firms are more likely to set science-based climate goals, to start disclosing through the Carbon Disclosure Project, and to cut their Scope 1 and 2 emissions. These effects are concentrated in high-emission, high-risk companies, showing that engagement is aimed at the areas of greatest material exposure. Yet there is no sign of change in Scope 3 emissions, no link to divestment decisions, and no spillover into other ESG areas. The picture is of an approach that can deliver measurable improvements on specific fronts, but leaves other major parts of the carbon footprint untouched.

The findings contribute to the wider debate on whether large, diversified asset managers can be effective stewards through private engagement alone. They suggest that such engagement can generate targeted, verifiable changes, especially when backed by robust analytical selection of companies. At the same time, the limits on emissions reductions, the absence of Scope 3 progress, and the cooperative voting stance underline that engagement is not a substitute for broader policy action. Standardised disclosure rules, clear Scope 3 requirements, and credible enforcement could make these investor efforts more effective. Without complementary regulation, even well-designed engagements are unlikely to deliver the scale of decarbonisation needed for global climate goals.

_________________

François Derrien is a Professor of Finance at HEC Paris.

Alexandre Garel is an Associate Professor of Finance at Audencia Business School.

Arthur Romec isan Associate Professor of Finance at Toulouse Business School.

Feng Zhou is an Assistant professor of Finance at Toulouse Business School.

This blog is based on a paper presented at the 3rd HKU Summer Finance Conference. Visit the event page to explore more conference-related blogs.

The ECGI does not, consistent with its constitutional purpose, have a view or opinion. If you wish to respond to this article, you can submit a blog article or 'letter to the editor' by clicking here.