The ECGI blog is kindly supported by

CoCo Bonds: Are They Debt or Equity? Do They Help Financial Stability? — Lessons from Credit Suisse NT1 Bonds

On Sunday, March 19, 2023, UBS Group AG agreed to take over Credit Suisse Group AG, a global banking giant that was struggling to survive, in an all-share transacEon brokered by the Swiss government. The takeover wiped out the value of AT1 CoCo bonds while giving a posiEve valuaEon to equity, which appeared to violate the absolute priority between debt and equity. This move caught bond investors off guard, and some were outraged. The event raises significant quesEons about CoCo bonds, and the following three are perhaps the most fundamental: Are CoCo bonds debt or equity? Why do banks issue them? Do they help financial stability?

Are CoCo Bonds Debt or Equity?

Confused Investors

The takeover resulted in the elimination of 13 outstanding AT1 CoCo bonds (also known as AT1 bonds) issued by Credit Suisse. The book value of these bonds totals 16 billion francs, which is equivalent to approximately 17.3 billion dollars. Although the AT1 bondholders received nothing in the takeover, the equity holders received 3 billion francs, which is worth about 3.2 billion dollars. This seems to violate the principle of absolute priority by making these bonds subordinate to equity in the bank's liability structure.

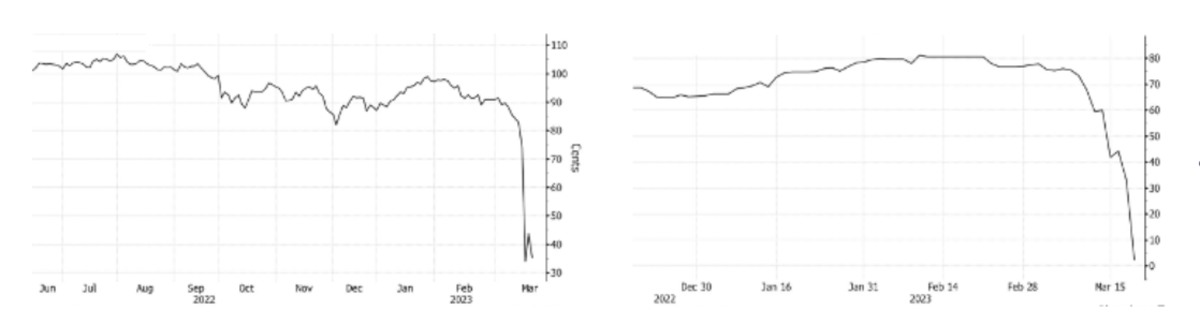

Bond investors were caught off guard and perplexed. They had apparently been valuing Credit Suisse AT1 bonds as junior debt prior to the takeover announcement. The price of a specific outstanding AT1 bond issued by Credit Suisse until the takeover is shown in the left panel of the figure below. Until March, the bond was priced just below par, and it was still valued above 30 cents on the dollar immediately before the takeover. However, following the takeover announcement, the price of such bonds plummeted to just a few cents on the dollar, as shown in the right panel of the figure below. It is evident that the risk of a wipeout was not factored into the price until it was publicly announced.

Source: Bloomberg

The investors of these AT1 bonds have incurred substantial losses. One cannot help but wonder who invested in the Credit Suisse AT1 bonds and how sophisticated they are. It is difficult to determine who held how much of these bonds, but we can glean some information from scattered reports in the media. For instance, it is widely reported that Saudi National Bank invested 1.4 billion francs in Credit Suisse towards the end of last year. On the day following the takeover announcement, Bloomberg reported that this Saudi bank had lost approximately $1 billion in about a month. However, it remains unclear how much of this loss is atributable to the AT1 bond wipeout. Qatar Investment Authority is another significant investor that partcipated in Credit Suisse's $2 billion convertable notes issuance in April 2021. Several major hedge funds, such as Pimco, Invesco, and BlackRock, also invested in Credit Suisse AT1 bonds. According to Bloomberg, Pimco held around $807 million, and Invesco held $370 million. BlackRock had $113 million in February, but it is uncertain how much it held by the end of the takeover. All these investors are expected to be knowledgeable and comprehend the risks associated with AT1 bonds. When investors were grappling with whether AT1 bonds were debt or equity, the Swiss regulator told them to read the prospectus.

Both Debt and Equity

AT1 bonds are contingent convertable (CoCo) bonds that are designed to functon as both debt and equity. An AT1 bond is a perpetual security with two triggers that cause the security to switch from debt to equity. It is important to note that the switch is mandatory, not optional, when it is triggered. The first trigger is the Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratio, which is the sum of common equity and retained earnings divided by risk-weighted assets. When the issuing bank's CET1 ratio drops to or below 7%, the AT1 bond is triggered to either write down or convert to a certain number of equity shares. The second trigger is the bank's regulator, which can decide the bond to be written down or converted.

Prior to being triggered, an AT1 bond operates like a typical debt security. The issuing bank raises funds at par value and makes fixed payments at regular intervals, much like the payment of interest on a debt instrument. In many countries, the fixed payments may be used to deduct corporate tax. In the event of the issuing bank's bankruptcy, the AT1 bond is senior to equity, similar to a debt instrument.

However, once triggered, the AT1 bond functions as equity. The periodic payments cease without a credit event, similar to the eliminaEon of dividends. The par value of the bond is wri\en down or converted into a specified number of common equity shares.

The AT1 bonds issued by Credit Suisse were subject to a 100% permanent write down, effectively converting the par value to zero shares of common equity. According to the Swiss banking regulator, the write-down was triggered due to the complete write-down of the bonds. The concept of these types of AT1 bonds, known as "bail-in" securities, was first proposed by Credit Suisse bankers Paul Calello and Wilson Ervin.[1] The term "bail-in" was coined as a counterpart to the unpopular "bailout" terminology. Calello was formerly the head of Credit Suisse's investment bank, while Ervin served as the chief risk officer.

AT1 bonds are a unique financial instrument that blurs the traditional distinction between debt and equity. They are designed to ensure that bondholders bear losses before equity holders in the event of the issuer's financial distress. If Credit Suisse's AT1 bonds are triggered by the 7% CET1 ratio, the bond value is written down to zero while the equity value on the book remains around 7% of the bank's risk-weighted assets. This means that AT1 bonds are subordinated to equity in the bank's liability structure. However, what makes AT1 bonds particularly confusing is that they retain seniority to equity if the bank goes into bankruptcy before the bonds are triggered. This is why Credit Suisse's AT1 bonds are still traded at a small positive price after the 100% write-down. Investors are speculating that if the takeover fails, the bank may go bankrupt, giving the AT1 bonds some value ahead of equity.

Why Do Banks Issue CoCo Bonds?

The global market for AT1 bonds, as reported by both the Wall Street Journal and Bloomberg, is valued at $275 billion. Many international banks have issued AT1 bonds, with some of the largest banks listed in the table below. Interestingly, UBS, the other large Swiss bank that is taking over Credit Suisse, has also issued a significant amount of AT1 bonds, which represent 28% of its CET1. These AT1 bonds, like those issued by Credit Suisse, also feature the 100% write-down provision. In terms of the total amount issued, HSBC has issued the most AT1 bonds. It has been reported that HSBC also includes the 100% write-down provision in its AT1 bonds, allowing them to be wiped out before equity in the event of a trigger. The global market for AT1 bonds spans across Europe, North America, and Asia, with the most banks issuing CoCo bonds located in China, India, the UK, and Switzerland.

Bank | HSBC | Barclays | UBS | BNP Paribas | Société Générale | Banco Santandar | Deutsch Bank |

AT1 ($bn) | 19.7 | 16.1 | 12.9 | 12.4 | 10.8 | 9.4 | 9.1 |

% of CET1 | 16.6 | 28.2 | 28.3 | 12.7 | 20.7 | 11.9 | 17.7 |

Source: Bloomberg | |||||||

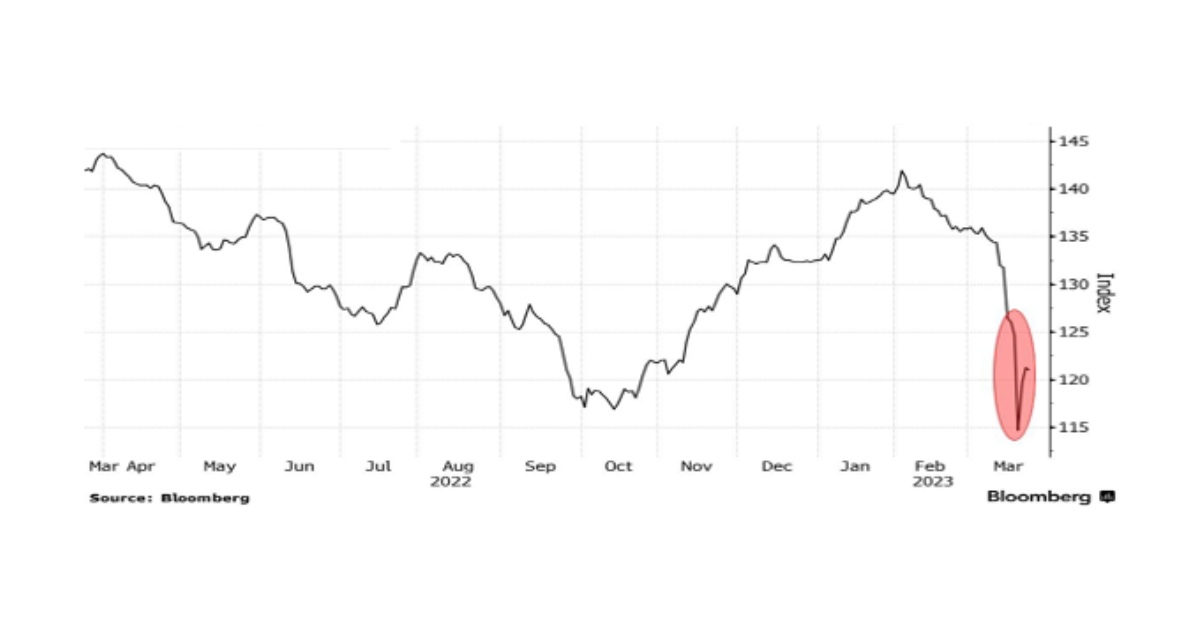

The wipeout of Credit Suisse's AT1 bonds caused a stir in the global AT1 market, as shown by the collapse of AT1 bond prices following the takeover announcement, as depicted in the Bloomberg global AT1 index figure below. However, the prices partially recovered in the days following the announcement as investors came to the realization that not all AT1 bonds have the 100% write-down feature. Most AT1 bonds either convert to certain shares of equity or partially write down when triggered. The sharp drop and recovery of prices indicates that AT1 bonds are complex securities, even for professional investors.

Arbitrage

Banks issue CoCo bonds because investors perceive them as debt instruments unti they are triggered. This was evident in the case of Credit Suisse AT1 bonds, which were priced as subordinate debt before the takeover announcement. Furthermore, the fixed periodic payments of CoCo bonds are typically treated as interest and are tax-deducEble in many countries. Hence, it is not surprising that banks uElize CoCo bonds as a means of raising debt, enabling them to obtain cheaper funding and prevent earnings diluEon.

Banks issue CoCo bonds also because regulators treat them as a type of equity. According to the Basel III Accord agreed upon by bank regulators worldwide, AT1 bonds are classified as "additional Tier 1" capital, which can be used to satisfy regional capital requirements above the Basel III CET1 capital requirement. Basel III mandates a 7% CET1 ratio for all banks, and 10% for large systematically important banks. However, many regional regulations require even more capital than what is required by Basel III.

Taking Switzerland as an example, Credit Suisse is required to maintain a Tier 1 ratio of at least 14.3%, a portion of which can be fulfilled by issuing AT1 bonds. However, the bank must also ensure that its true CET1 ratio, which uses only common equity and retained earnings, is at least 10%, in compliance with Basel III regulations. Allowing AT1 bonds as additional capital enables Credit Suisse to lower its average cost of capital, as it can avoid issuing more common equity. Therefore, Credit Suisse benefits from using AT1 bonds as equity for regulatory purposes.

It is evident that Credit Suisse utlized AT1 bonds both as debt and equity. By using the bonds as debt, the bank obtained cheaper funding, and by using them as equity, it met regulatory capital requirements. It does raise questions as to whether Credit Suisse was using CoCo bonds to arbitrage among capital markets, tax policy, and banking regulations. However, Credit Suisse is not alone in doing this, considering the size of the global AT1 market, and other banks may have also used this approach to optimize their funding and regulatory capital requirements

No CoCo from U.S.

Although many international banks have issued CoCo bonds, none of the U.S. banks have done so. It is worth examining the regulatory landscape surrounding CoCos in the U.S. to gain some insight. The U.S. banking sector operates under a different set of rules and regulaEons than its internaEonal counterparts, which may explain why CoCos have not been embraced by U.S. banks. By exploring these regulatory differences, we may gain a better understanding of why U.S. banks have avoided issuing CoCo bonds.

CoCo bonds in the U.S. were subject to intense debates during 2009-2011. A group of academics advocated for the use of CoCo bonds as regulatory capital,2] while major banks like Goldman Sachs supported the idea and pushed regulators to adopt it. However, there were also concerns raised by others.[3] The Dodd-Frank Act, which became law in 2010, included Section 115 requiring U.S. regulators to conduct a study on CoCo bonds for bank regulation and report their findings to Congress within two years.

The United States agreed to the Basel III Accord published in late 2010, which does not permit banks to use CoCo bonds in the CET1 requirement but allows regional regulators to consider certain CoCo bonds as “additional Tier 1” or “Tier 2” capital to meet additional regional capital requirements. In 2012, the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) reported to Congress that U.S. regulators would not use CoCo bonds as regulatory capital and instead leave them as a private sector innovation. This stance likely discourages U.S. banks from engaging in arbitrage between banking regulation and the capital market. It is worth investigating whether this is the primary reason U.S. banks are avoiding CoCo bonds.

The tax advantage is an important consideration in the strategic decisions that banks make regarding their liability structure.[4] However, CoCo bonds do not enjoy the same tax advantage in the US as they do in Europe and Asia. According to Section 163(l) of the Internal Revenue Codes, the fixed payments of CoCo bonds are unlikely to be tax-deductable. This tax rule states that a security is a disqualified debt instrument if (1) a substantial amount of the principal and interest of the security is required to be paid in or converted into the equity of the issuer, (2) a substantial amount of the principal or interest is required to be determined by reference to the value of such equity, or (3) the indebtedness is part of an arrangement that is reasonably expected to result in a transaction described in (1) or (2).

The fact that all CoCo bond issuers are located in countries that treat these bonds as regulatory capital and tax-deductible, while no U.S. banks have issued any of these bonds, raises the question of whether CoCo bonds serve primarily as a tool for arbitrage among banking regulation, tax policy, and the capital market. This issue warrants further investigation. It's important to note that there are no regulations prohibiting U.S. banks from issuing CoCo bonds, and it is a decision made by these banks to refrain from doing so. Therefore, any economic theory that explains why banks issue CoCo bonds must also account for why U.S. banks choose not to issue them.

Do CoCo Bonds Help Financial Stability?

The main selling point for CoCo bonds is that they can improve financial stability and protect taxpayers. Mark Flannery succinctly summarizes this selling point: “Academics and regulators conjectured that including sufficient CoCos in a bank’s capital structure could substantially insulate taxpayers from private investment losses.”[5] Others have echoed the view that CoCo bonds can help solve the too-big-to-fail problem.[6] The logic behind this selling point is that because CoCo bonds function like debt and are cheaper than equity, banks may prefer issuing them to obtain additional capital instead of issuing equity. If the bank's capital falls below a certain threshold, the CoCo bonds are triggered, allowing for timely private recapitalization and avoiding the need for government intervention and taxpayer assistance. This logic is certainly compelling.

However, the takeover of Credit Suisse by UBS has once again put Swiss taxpayers at risk, 15 years after they had to bail out UBS. As part of the takeover agreement, the Swiss National Bank provided UBS with a 100-billion-franc liquidity line, and the Swiss Department of Finance offered a 9-billion-franc guarantee for potential losses on Credit Suisse assets. Obviously, the 16- billion-franc CoCo bonds failed to provide protection to Swiss taxpayers from bank risks. A recent poll revealed that three-quarters of the Swiss population is dissatisfied with the government-brokered takeover. The selling point of CoCo bonds appears to have flawed logic.

It's crucial to comprehend why Credit Suisse's AT1 bonds didn't perform as advertised by their proponents.

CET1 Ratio

It's worth noting that the Credit Suisse AT1 bonds were triggered by the regulator rather than the CET1 ratio. Just four days before the Sunday takeover, FINMA confirmed that Credit Suisse met the higher capital and liquidity requirements for systemically important banks. The CET1 ratio was 14.1%, more than double the 7% ratio for the trigger. However, on Sunday, the regulator decided that the bank had to be taken over by its rival and triggered the write-down of AT1 bonds. Swiss Finance Minister Karin Keller Sutter stated that “Credit Suisse would not have survived Monday.” If both the Swiss banking regulator and the government were correct about Credit Suisse, then the AT1 bonds did not recapitalize the bank in a timely manner. The write-down occurred so late that the bank had to be taken over by another bank with the assistance of the government. This may be one of the reasons why the AT1 bonds failed to protect taxpayers from bank risks.

The delayed recapitalization of Credit Suisse highlights a problem with the CET1 ratio. As an accounting measure based on book values, it does not accurately reflect the status of a bank and can be manipulated by bank management. Similar experiences with the CET1 ratio have been observed in the US. In the month before Bear Stearns was taken over by JPMorgan Chase with public assistance, its estimated CET1 ratio was 13.5%. In the month before Lehman Brothers went bankrupt, its CET1 ratio was 10.1%. Right before Silicon Valley Bank was closed by the FDIC, its CET1 ratio was 15.4%. If the CET1 ratio trigger is ineffecEve, banks relying on CoCo bonds for recapitalization are left to the discretion of regulators to decide when to recapitalize. However, as we have observed in the past, regulators often act too late, and by the time they intervene, the bank is no longer a viable going concern without taxpayer support.

The ineffectiveness of accounting triggers has been anticipated by many. Some academics have suggested a market trigger, which would be based on the market value of equity.[7] They argue that a market trigger would be timely, objective, and difficult to manipulate. While these arguments appear to be reasonable, market triggers have a fundamental issue, as pointed out by others[8] With market triggers, CoCo bonds and bank stocks can have multiple equilibrium prices or no equilibrium price at all. In either case, information about the bank's value is lost, leading to significant pricing uncertainty, which could be exploited by market manipulators.

These concerns are supported by economic experiments.[9] As a result, academics have attempted to develop alternative trigger mechanisms, but none has proven to be practical thus far.

Incentives

Another crucial issue concerning the role of CoCo bonds in financial stability is the incentives they provide to bank management. It is important to differentiate between the conversion that dilutes equity value and the conversion that subsidizes equity. If bank managers work for or as shareholders, the CoCo bonds with diluEve conversion punish managers for running the bank down to the trigger, while the CoCo bonds with equity-subsidizing conversion reward them for doing so. Most theoreEcal analyses recognize that dilutive conversion is a desirable feature and assume it as the starting point for their analyses. CoCo bonds with write-downs clearly subsidize equity holders when triggered. The 100% write-down of Credit Suisse AT1 bonds represents a wealth transfer from AT1 bondholders to equity holders. Further research is necessary to determine whether AT1 bonds provide incentives to managers to run banks down.

While some studies have attempted to analyze the incentives that CoCo bonds create for bank management,[10] many have overlooked the strategic responses of banks when it comes to their liability structure choices. It is well-established that a leveraged bank has risk-taking incentives similar to those of a leveraged firm[11] Although high capital requirements may seem like a solution for removing these incentives, recent research on bank liability structure has found that risk-taking incentives persist if banks adjust their liability structure optimally in response to changes in capital requirements[12]. Therefore, to fully understand the incentives created by CoCo bonds, we need to investigate how banks make optimal choices regarding the use of CoCo bonds as part of their overall liability structure.

Trigger Event

For CoCo bonds to contribute to financial stability and protect taxpayers from bank risks, it is crucial that triggering these bonds has a positive impact on the bank. In other words, the bank's performance and value should improve adter a CoCo bond trigger event. If triggering the bonds is seen as beneficial, banks would not try to avoid hitting the triggers. While trigger events have been rare in the past, a study of Liability Management Exercises in Europe suggests that such events can increase bank value, and that bank management is unlikely to avoid them.[13]

However, the Credit Suisse AT1 bond trigger event tells a different story. The AT1 bonds remained untriggered until the bank became non-viable without public assistance. At the trigger event, the bank was taken over at a much lower value, and its assets were marked down by 56 billion francs as badwill.

The near-trigger experience of Deutsche Bank in 2016 further highlights the negative perception of a trigger event by the market. When the bank's CET1 raEo was close to the trigger point for some of its CoCo bonds, the bank's CDS spread spiked to 248 bps and its stock price plummeted by over 40% in just two months. To avoid triggering the bonds, Deutsche Bank offered to buy back €3 billion and $2 billion of its CoCo bonds. CEO John Cryan later expressed his frustration with CoCo bonds, stating that “They are not a great instrument. We shouldn't really need them going forward. When you want them to be debt, they are equity, and when you want them to be equity, they are debt.”

Better Than Regular Bonds

AT1 bonds may have played a role in enabling Credit Suisse to find a buyer and avoid nationalization or liquidation, which could have caused uncertainty and potential damage to Swiss taxpayers. To illustrate this, consider the basic numbers in the balance sheet, regulatory filings, and the takeover terms of Credit Suisse, as listed in the table below. After factoring in the 56-billion-franc badwill and wiping out the 16-billion-franc AT1 bonds, the equity value amounts to (531 – 56) – (386 – 16) = 5 billion francs, which can be seen as the maximum price UBS was willing to pay. If the 16-billion-franc AT1 bonds were regular bonds and not able to be wiped out, the equity value would have been (531 – 56) – 386 = –11 billion francs, making it highly unlikely for anyone to buy.

Balance sheet: | Assets | 531b | Liabilities | 386b | Equity | 45b |

Regulatory filing: | RWA | 251b | CET1 ratio | 14.1% | Leverage | 5.4% |

Takeover: | AT1 | 16b | UBS | 3b | Badwill | 56b |

UBS must provide enough equity to Credit Suisse to meet the CET1 ratio and leverage ratio requirements set by FINMA at 14.3% and 5%, respectively. Based on the information presented in the table above, UBS must inject a minimum of half a billion francs in capital. UBS initially offered one billion francs, which would have given Credit Suisse a CET1 raEo of 14.5% and a leverage ratio of 5.55%, both slightly above the required ratios set by Swiss banking regulations. However, this offer was rejected. The final price of 3 billion francs exceeds the minimum capital requirement and gives Credit Suisse a CET1 ratio of 15.3% and a leverage ratio of 5.86%, which are well above the ratios required by FINMA.

The basic math outlined above highlights how the elimination of AT1 bonds played a crucial role in maintaining financial stability by enabling the acquisition of the struggling Credit Suisse.

Nationalizing or liquidating such a large bank could have caused significant damage to the global banking industry. Therefore, in this context, AT1 bonds are a more effective tool for stabilizing the banking industry than the regular bonds that cannot be written down or converted to equity.

Better Than Equity?

The debate on CoCo bonds should not be limited to their superiority over regular bonds, but whether they are a better form of capital than equity. While an empirical study shows that CoCo bond issuance can reduce CDS spread of issuers,14 it remains unclear if CoCo bonds are better for bank stability than equity. The finding may reflect the fact that CoCo bonds are junior to the bonds underlying CDS. In contrast, if a bank issues more common equity instead of CoCo bonds, it could lead to a drop in CDS spread, possibly even more. Moreover, the same study indicates that write-down CoCo bond issuance can raise the issuer's stock price, yet this does not necessarily mean that CoCo bonds are superior to equity as a form of capital. Rather, it may be due to the fact that write-downs subsidize equity.

While AT1 bonds were useful for the takeover of Credit Suisse, it is debatable whether CoCo bonds are a superior form of capital compared to common equity. Consider if Credit Suisse had issued 16 billion francs of common equity instead of AT1 bonds. In this scenario, there would have been no need for regulators to decide when to wipe out the bonds as the market would have gradually adjusted the value of common equity in response to information about the bank. Investors would not have been caught off guard by a complicated security, reducing volatility and uncertainty in the global bond market. Although the per-share value of Credit Suisse equity would have been lower, the total equity value would have been the same. Moreover, Credit Suisse would not have been able to exploit discrepancies in banking regulation, tax policy, and capital markets. This could be a preferable scenario, and further research is needed to determine which security, CoCo bond or common equity, leads to greater stability in financial markets and institutions.

Summary

CoCo bonds are a unique hybrid security that combines the characteristics of debt and equity. They function as debt until they are either converted into equity or written down to lose value alongside or before equity. Banks can use CoCo bonds to exploit discrepancies among capital markets, tax policies, and banking regulations, if investors price them as debt, governments treat them as tax-deductible, and regulators count them as equity. CoCo bonds do not effectively protect taxpayers from bank risks, especially in light of the inactive Tier 1 ratio and slow regulators. Although CoCo bonds may be more useful than non-convertible, non-written- down bonds for rescuing unviable banks, it remains uncertain whether they are more effective than common equity as capital for ensuring financial stability. Further research is necessary to address these issues.

-------------------------------------

By Zhenyu Wang, the Edward E. Edwards Professor of Finance at the Kelley School of Business, Indiana University. He was formerly a Vice President and the Head of the Financial Intermediation Function at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

To read Zhenyu Wang's abridged version and blog article "Are CoCo bonds better than common equity as capital for financial stability?", click here.

To watch Prof. Zhenyu's lecture entitled “CoCo Bonds: Are They Debt or Equity? Do They Help Financial Stability?” for The Institute for Corporate Governance Public Lecture Series, click here.

If you would like to read further articles from the 'Banking Crisis 2023' Blog edition, click here.

The ECGI does not, consistent with its constitutional purpose, have a view or opinion. If you wish to respond to this article, you can submit a blog article or 'letter to the editor' by clicking here.

[1] “From bail-out to bail-in,” The Economist, January 28th, 2010.

[2] Flannery (2009): “Stabilizing large financial institutions with contingent capital certificates,” University of Florida; Squam Lake Working Group (2009): “An expedited resolution mechanism for distressed financial firms: Regulatory hybrid securities,” Council on Foreign Relations, Center for Geoeconomic Studies; Calomiris and Herring (2011): “Why and how to design a contingent convertible debt requirement,” University of Pennsylvania.

[3] Sundaresan and Wang (2010): “On the design of contingent capital with a market trigger, Columbia University and Federal Reserve Bank of New York; Admati, DeMarzo, Hellwig, and Pfleiderer (2010): “Increased-liability equity: A proposal to improve capital regulation of large financial institutions,” Stanford University.

[4] Gambacorta, Ricotti, Sundaresan, and Wang (2021): “Tax effects on bank liability structure.” European Economic Review 138.

[5] Flannery (2014): “Contingent capital instruments for large financial institutions: A review of the literature,” Annual Review of Financial Economics 6:225-240.

[6] Flannery, (2002): “No pain, no gain? Effecting market discipline via reverse convertible debentures,” University of Florida; Flannery (2009): “Stabilizing large financial institutions with contingent capital certificates,” University of Florida.

[7] Sundaresan and Wang (2015): “On the design of contingent capital with a market trigger,” Journal of Finance 70:881--920.

[8] Davis, Korenok and Prescott (2014): “An experimental analysis of contingent capital with market-price triggers,” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 46:999–1033.

[9] Sundaresan and Wang (2015): “On the design of contingent capital with a market trigger,” Journal of Finance 70:881--920.

[10] Berg and Kaserer (2015): “Does contingent capital Induce excessive risk-taking?” Journal of Financial Intermediation 24:356–385; Chan and van Wijnbergen {2014}: “Cocos, contagion and systemic risk,” Tinbergen Institute; Gamba, Gong, and Ma (2023): “Non-dilutive CoCo bonds: a necessary evil,” University of Warwick; Himmelberg and Tsyplakov (2020): “Optimal terms of contingent capital, incentive effects, and capital structure dynamics,” Journal of Corporate Finance 64:1016–1035.

[11]AdmaC, DeMarzo, Hellwig, and Pfleiderer (2018) “The leverage ratchet effects,” Journal of Finance 73:145–198.

[12] Sundaresan and Wang (2022): “Strategic bank liability structure under capital requirements,” Management Science, forthcoming.

13]Boris Vallee (2019): “Contingent capital trigger effects: evidence from liability management exercises,” Review Corporate Finance Studies 8:235-259.

[14] Avdjieva, Bogdanovaa, Bolton, Jiang, Kartasheva (2020): “CoCo issuance and bank fragility,” Journal of Financial Economics 138:593-613.