The ECGI blog is kindly supported by

When Nature Fails, Markets Follow

A review of the lecture “Nature and Biodiversity Loss: Economic and Financial Implications” by Professor Johannes Stroebel 10th February 2026.

“Destroying nature means destroying the economy,” – yet this claim invites a difficult question. If biodiversity has declined dramatically over the past half-century, why has global economic output continued to grow?

In the tenth lecture of the NBS–PRI–ECGI Public Lecture Series, Johannes Stroebel of NYU Stern confronted this tension directly. His aim was neither to dramatise nor to downplay biodiversity risks, but to clarify them. Nature loss and climate change, he argued, are distinct economic forces that interact in important and amplifying ways. Understanding both their differences and their interactions is essential for policymakers and financial markets.

Stroebel structured his lecture around three questions: how nature loss and climate change relate to one another, how biodiversity loss generates physical economic risk, and whether these risks are reflected in asset prices.

Nature and Climate: Distinct but Intertwined

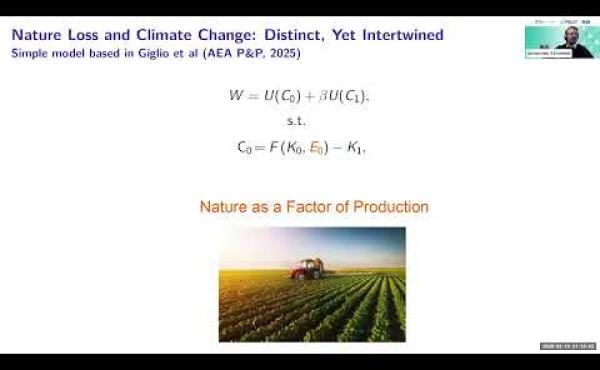

The first part of the lecture introduced a deliberately simple economic model to clarify how nature and climate interact. Climate change is typically modelled as a damage function. Output is produced, and then part of it is destroyed by physical hazards such as floods, hurricanes, or wildfires.

Nature operates differently. It is not just exposed to damage, it is a direct factor of production. Food, timber, pollination, water filtration, genetic resources for pharmaceuticals, these ecosystem services are inputs into economic activity itself.

The distinction matters. Climate change reduces what is produced. Biodiversity loss alters how production works in the first place.

Yet the two crises are deeply intertwined. Nature acts as a carbon sink, reducing atmospheric emissions. It also provides adaptation, mangroves, for example, reduce storm damage to coastlines. Destroy nature, and the economy loses both mitigation and protection.

This creates what Stroebel termed a “twin crisis multiplier.” Climate change accelerates biodiversity loss. Biodiversity loss weakens carbon sequestration and adaptation, amplifying climate damage. The feedback loop means that analysing either crisis in isolation risks understating their combined economic effects.

One implication is that even if certain ecosystem services can be replaced by physical capital, such substitution is rarely neutral. A wetland that filters water does so while absorbing carbon. A mechanical filtration plant may replicate the service, but at an energy cost that increases emissions. Replacing nature with capital may preserve output in the short run while intensifying long-term climate risk.

The broader message was conceptual clarity. Climate and biodiversity are not identical challenges. But once their interaction is properly specified, the economic case for addressing them together becomes more compelling.

Ecosystem Fragility and Keystone Species

The second part addressed a more subtle question. Why do some species losses appear economically negligible, while others have dramatic consequences?

Drawing on established ecological literature, he proposed modelling ecosystems as hierarchical systems. At the top level are distinct ecological functions, pollination, pest control, seed dispersal, nutrient cycling. These functions are complementary. An ecosystem cannot compensate for the loss of pollination by increasing pest control. Each function must be present.

Within each function, however, multiple species may provide similar services. Here, biodiversity improves productivity through what ecologists call niche differentiation. Species crowd out their own kind more than others, allowing more efficient use of resources. Empirically, the relationship between biodiversity and productivity is increasing but concave: the first few species add significant value, later additions contribute less.

This structure generates a powerful asymmetry. Early species losses may have limited impact because of functional redundancy. The system appears resilient. But each loss reduces redundancy and increases fragility. Eventually, a function may become dependent on very few remaining species, a keystone species. Losing it can cause a sharp, nonlinear collapse in ecosystem output.

The absence of visible macroeconomic damage from past biodiversity loss, therefore, does not imply safety. It may reflect the fact that ecosystems began with high redundancy. The real risk lies in the erosion of that buffer.

This framework also complicates biodiversity offsetting. Unlike carbon, biodiversity lacks a universal unit of account. A tonne of CO2 has similar atmospheric effects regardless of where it is emitted. A species lost in one ecosystem cannot be straightforwardly offset by protecting a similar species elsewhere. Its economic value depends on context, whether it is redundant or keystone within that specific system.

For regulators and investors, this raises uncomfortable questions about the design of offset schemes and biodiversity metrics. Measuring nature in aggregate scores may obscure the very fragility that matters most.

Is Biodiversity Risk Reflected in Markets?

Finally, the discussion shifted to markets. If biodiversity loss generates physical and regulatory risk, are those exposures reflected in asset prices? A new biodiversity news index, derived from media coverage, provides a way to test this. Countries with uneven biodiversity depletion across functions—hence greater ecosystem fragility—experience slightly larger movements in sovereign credit default swaps when negative biodiversity news emerges. The magnitudes are small, measured in basis points, but statistically discernible.

Firm-level analysis yields similar signals. Approximately 5% of US firms now disclose biodiversity risk in 10-K filings, up from around 1% a quarter-century ago. Exposures vary by sector: energy, utilities, real estate and agriculture report significant transition risk, while pharmaceuticals highlight dependencies on biological inputs. Notably, renewable energy firms—often positioned as climate champions—frequently cite biodiversity-related regulatory constraints. Wind, solar and hydropower infrastructure can disrupt habitats and species, revealing a tension between climate mitigation and nature protection.

Market data suggest that biodiversity risk is beginning to be priced, though perhaps only partially. Survey evidence indicates that investors themselves doubt pricing is adequate. Whether that reflects genuine underestimation or simply heightened awareness among respondents remains unclear.

What emerges is a field in transition. Biodiversity economics is not yet as mature as climate finance. Data are imperfect, models simplified, and valuation contentious. Yet the conceptual advances are significant, with nature being not merely a background condition; it is a productive input, a buffer against climate damage, and a source of nonlinear systemic risk.

Nonlinear Risks and Measurement Challenges

The discussion throughout the lecture, led by Tessa Younger, shifted the focus from theory to implementation. If biodiversity risk is structurally different from climate risk, how should financial institutions incorporate it into existing risk frameworks? Conventional models assume measurable exposures and comparable units. Biodiversity offers neither in a straightforward way.

Particular attention was given to modelling assumptions. If ecological degradation does not unfold in smooth increments, stress-testing frameworks may struggle to capture its distributional properties. The challenge is less about acknowledging risk and more about adapting financial tools to risks that are context-dependent and system-specific.

Restoration raised a related practical question. Could large-scale rehabilitation meaningfully alter firms’ emissions profiles or regulatory exposure? While ecological recovery can strengthen resilience, it does not automatically neutralise the economic incentives that drive degradation. The policy design question, therefore, is not only about restoration, but about embedding nature considerations into capital allocation and supervision.

The exchange ultimately returned to governance. How should regulators treat ecosystem fragility within financial stability mandates? How should disclosure frameworks evolve when biodiversity lacks a universal metric? And how can market instruments avoid oversimplifying ecological complexity?

-----------------------------------

This lecture is part of the NBS-PRI-ECGI Public Lecture Series, a global initiative on sustainable business. Nanyang Business School (NBS), in collaboration with the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) and the European Corporate Governance Institute (ECGI), launched this series to foster knowledge exchange between academics, practitioners, and policymakers. As part of this initiative, leading academics present cutting-edge research on sustainability topics, while industry experts moderate discussions, providing real-world insights and facilitating dialogue between research and practice.