The ECGI blog is kindly supported by

What to Expect from Sustainability Disclosures

A review of the lecture “Is sunlight the best disinfectant? What to expect from sustainability disclosures” by Professor Christian Leuz 3rd June 2025.

In his recent lecture for the NBS-PRI-ECGI series, Professor Christian Leuz (Chicago Booth School of Business) tackled one of the most consequential assumptions in corporate governance: that transparency alone can realign corporate behaviour with societal goals. Through a meticulous review of disclosure mandates, empirical studies, and novel metrics, Leuz offered a more calibrated view—one in which transparency regulation, though valuable, is neither universally effective nor sufficient in driving changes in corporate behavior.

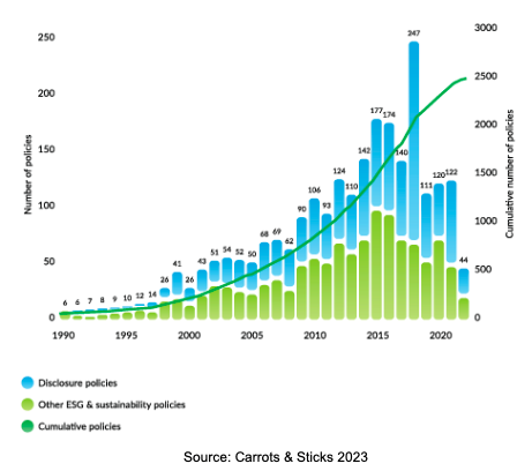

The global embrace of sustainability reporting has been swift and expansive. As shown in Leuz’s opening slides, the number of mandatory disclosure regimes worldwide has surged in recent years, with jurisdictions such as the EU, UK, and California leading the charge. These rules have a central logic: that by requiring companies to expose their sustainability footprints, regulators can prompt capital markets and society to hold them accountable. The image is that of sunlight as a disinfectant—but Leuz presses the analogy: under what conditions does sunlight actually work?

Leuz suggested that disclosure regulation gained its prevalence in addressing sustainability challenges likely because it can be a less intrusive means compared to conventional regulation to trigger responses among those with the power to influence firms—investors, consumers, watchdogs, regulators, which in turn induces firms to change their behaviour. For this, the disclosed information needs to be comprehensible, timely, credible, and sufficiently salient to provoke action.

The case of hydraulic fracturing in the United States provides an instructive example. Leuz and his co-authors Bonetti and Michelon studied the introduction of chemical disclosure mandates across several states and linked these to changes in water quality. The result: a 9–15% reduction in local water pollution. Importantly, they show that the disclosure worked because it enabled communities and social movements to exert public pressure. Here, transparency worked.

But Leuz also makes clear that such outcomes are not guaranteed. The outcomes depend crucially on the responses of those who receive the information, and these responses can be difficult to anticipate. Moreover, in politicized environments, they can lead to unintended responses and consequences. For this reason, he proposes to focus on areas with clear and large negative externalities. Rather than diluting mandates across dozens of topics, Leuz argues for targeting disclosure where harm is measurable and the feedback loop is plausible.

Nowhere is this focus more urgently needed than in the realm of climate change. Leuz presented recent work, co-authored with Greenstone and Breuer, that calculates firm-level carbon damages by applying a standard estimate for the monetary damages from carbon emissions to firms’ reported emissions, essentially quantifying the social costs of corporate activities. They then relate these social costs to the private value generated, as measured by the firms’ operating profit. They show that, on average, the corporate carbon damages are substantial, amounting to 44% of firms’ operating profits. However, these damages are very skewed: as expected, industries such as energy or materials produce outsized carbon damages. Perhaps more surprisingly, they also show that there is a tremendous variation in carbon damages even within narrowly defined subindustries or peer groups.

The implications are immediate. Variation in carbon damages within narrow industries suggests opportunities for high-damages firms to improve. One force that could lead to such improvements is peer benchmarking. It could work by firms learning from each other, but also via external pressure, be it from investors, rating companies, or the public.

And yet, it is important to recognize the limits of sustainability disclosure in addressing sustainability issues. Leuz discussed investor survey data showing that only a minority of asset managers are willing to accept lower returns in exchange for environmental or societal benefits. Without complementary regulation, such as carbon pricing and green taxation, disclosure alone will not close the incentive gap created by externalities. Even the best data cannot force a shift if the economic structure and incentives remain unchanged.

Leuz’s own recommendations are pragmatic. If the goal of the disclosure or transparency regime is to change corporate behaviour, then we should first focus on major externalities and try to identify metrics that can be reported in a cost-effective way. Importantly, he suggests that sustainability disclosure regimes should be designed to serve as a foundation or bedrock for other sustainability policies.

During the post-lecture discussion, Leuz responded to comments from Nathan Fabian (Principles for Responsible Investment) regarding investors’ latest views on incorporating sustainability information into capital market decisions. He reiterated that we should not conflate risk-to-firm disclosures with externality-focused reporting, particularly when designing and assessing sustainability disclosure regimes in the private versus public sector. When comparing the effectiveness of sustainability reporting regulation across countries, he highlighted the importance of the operational environment of reporting regulation, such as enforcement mechanisms and auditing requirements, which often receive less attention compared to reporting standards. The audience’s concerns echoed a broader policy tension: how to balance the appetite for granular disclosure with the need for streamlined, decision-useful information.

The appeal of transparency as a non-coercive policy tool is undeniable. But without an understanding of where, how, and for whom it works, the risk is that sustainability disclosure becomes a sprawling, burdensome exercise. The challenge ahead is to clarify not only what sustainability information policymakers should prioritize, but also what we, as a society, intend to do with the information once we have it.

-----------------------------------

This lecture is part of the NBS-PRI-ECGI Public Lecture Series, a global initiative on sustainable business. Nanyang Business School (NBS), in collaboration with the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) and the European Corporate Governance Institute (ECGI), launched this series to foster knowledge exchange between academics, practitioners, and policymakers. As part of this initiative, leading academics present cutting-edge research on sustainability topics, while industry experts moderate discussions, providing real-world insights and facilitating dialogue between research and practice.