The ECGI blog is kindly supported by

Abolishing the UK Corporate Governance Code: a bold tonic or a measure too far?

In July 2022, ECGI published a blog by Brian Cheffins, S.J. Berwin Professor of Corporate Law at the University of Cambridge, ‘A bold governance tonic for UK equity markets’ The blog draws on papers published by Brian Cheffins with Bobby Reddy such as ‘Will Listing Rule Reform Deliver Strong Public Markets for the UK?’. The main arguments are that the FCA’s changes to the Listings Rules will not reverse the decline in listings on the London Stock Exchange because founders’ rights will still be limited, SPACs may have incentives to re-list on overseas exchanges post-acquisition, and the change in the minimum permitted free float from 25% to 10% of shares outstanding is immaterial as most firms have a free float significantly in excess of 25% anyway. They also argue that exits from the LSE may be caused by the regulatory burden of the UK Corporate Governance Code, which premium listed firms are required by the Listing Rules to follow and from which the Code’s overseer, the Financial Reporting Council, permits only temporary deviations. They mention the Code’s duplicative nature, claim its emphasis on stakeholder protection is misguided and suggest that a simple Listing Requirement that ‘’companies divulge pivotal specified corporate governance arrangements’’ would be an adequate substitute. They conclude that the Code should be abolished.

We will summarise some relevant facts before turning to policy issues raised by the blog.

What do the data say?

There is broad consensus among academics, regulators and policymakers as to the condition of the patient. Trends show that UK public equity markets have been in decline over the past 20 years, with the number of domestic listed companies falling from 2,355 to 1,615.[1] This is a substantial fall even relative to the long-term declines in the number of listed companies in several other European equity markets.

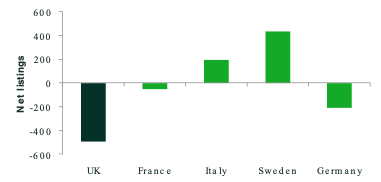

Figure 1 Net changes in the number of listed companies between 2012 and 2022

Note: Each net listings value is calculated as the number of listings in 2022 minus the number of listings in 2012.

Source: Stock exchange websites; WFE.

The fall in the stock of listed companies is driven both by companies exiting public markets and by a fall in the number of IPOs.

Recent policy reform

Unsurprisingly given the data above, there is considerable appetite for reform among market participants and policymakers.

Subsequent to the changes discussed by Cheffins and Reddy, the FCA proposed simplifying the UK listing regime by abolishing the existing two-tiered approach of Premium and Standard listings in favour of a single set of eligibility criteria, mandatory ongoing obligations and a set of supplemental voluntary obligations. Then the Austin Review into UK secondary capital raising recommended increasing the maximum proportion of share capital that listed companies can raise without the need to undertake a full rights issue;[2] increasing retail investor involvement in capital raisings; reducing regulatory involvement in large fundraisings; and improving the legal structures available for listed companies doing secondary raisings.

Issue: Will reforms to Listing Rules fail to boost listing?

Reforms have progressed since Cheffins and Reddy did their work. We consider the latest position rather than restrict ourselves to their concerns, though they certainly raise some interesting conceptual issues.

Firms list to get capital. There is no reason ex ante to suppose that a firm will be better off with a public listing or private equity. Private equity has specific attributes which may confer advantages that go beyond avoidance of compliance costs, meaning its growth is unlikely to be solely the result of deficiencies in Listing Rules. So it does not make sense to compare the extent of listing before PE became a viable alternative with the extent of listing now and conclude that there is something wrong with the Listing Rules. It may just be that an alternative that is preferable to many has come along: Listing may even be Betamax to PE’s VHS.

There would be a problem with the Listing Rules if firms would like to be listed and investors would like them to be listed on terms that are much lighter than the rules require. Cheffins and Reddy do not appear to make this argument when discussing the Code specifically. Rather, they say that “The present day Code is inconsequential in part because publicly traded companies would likely adopt key Code features in the absence of the Code.” Nor do they claim unequivocally that public listing should be promoted due to its positive externalities – a sense of public involvement in the wealth creation process and sharing of the wealth, or the provision of visible market prices for stocks, although they mention that ‘’a case in favour of bolstering the stock market can be developed’’ by reference to such benefits.

The anticipated failure of the changes to the Listing Rules is somewhat speculative. It is worth waiting to see the effects of the changes in practice, especially as the changes discussed are now not the only ones in train. In addition to the FCA’s planned single-tier listing approach, the recommendations of the Austin Review are under consideration as described above. Perhaps the overall set of changes will make a big difference. Why not study the effects of all the reforms and undertake more research on the supply of and demand for listing information?[3]

On the other hand, it is legitimate to ask whether greater disclosure requirements should be imposed on private companies if they form a materially larger part of the economy. For example, there is a concern that banks’ exposures to large, opaque private companies might threaten financial stability. Closer alignment of the requirements for private and public companies might also reinvigorate public markets, increasing any social benefits they offer.

Issue: Why have corporate governance requirements at all?

Would removal of the Code lead to more listing or does it make sense to get rid of the Code whether or not this would increase listing?

Realistically, the incremental compliance costs arising from the Code are unlikely to be material in the context of the finances of a publicly listed company and, if these were also faced by a company’s rivals, they would presumably be passed through to its customers in prices. The likely low level of incremental compliance costs is supported by evidence that even if there were no code most firms would do most of what the Code requires. It is also supported by the overlaps between what the Code says and what the Listing Rules in any case require. Thus, replacing the Code with a tweak to the Listing Rules could be sensible but, contrary to the view of Cheffins and Reddy, it is unlikely to solve the problem of limited listing, if a problem it be. Indeed, costs of complying with corporate governance codes are just one among several other factors (e.g. lower valuations relative to the US, inadequate visibility for listed companies, limited retail investor involvement, and a dearth of supply of companies to name a few) that are cited as the cause of the decline of the UK publicly listed model.

Even so, is a separate Code is needed? While the interests of shareholders and other stakeholders are not necessarily in conflict, Cheffins is surely right that shareholders concerned with maximising risk-adjusted returns may not champion stakeholder protection. Also, it is not clear to what extent the existence of the Code alone has prevented abusive governance. For example, it is generally held that the version of the Code in force during 2016-2018 did not constrain poor behaviour in the ways it was intended to at Carillion.

Generally, though, the case for terminating the Code is not that this would help stimulate more listings. Rather it is the principle of regulatory simplification and the need for regulations to pass a sensible cost/benefit test, given that any incremental benefits of the Code are hard to identify. Be that as it may, we believe that good governance, whether it be a tweak to the listing rules or some other mechanism that brings it about, bears important societal benefits as described in our recent report for the European Contact Group.

[1] Oxera analysis of LSEG data. Includes both LSE main market and AIM.

[2] Existing pre-exemption requirements permit companies to issue up to 10% of issued share capital for any purpose, with up to a further 10% available for an acquisition or specified capital investment. These rules were temporarily relaxed in 2020 as a rule of Covid-19 pandemic. As well as recommending these temporary changes be made permanent, the Austin review has recommended that companies be permitted to request a disapplication of the pre-emption rights over a period of time, subject to shareholder approval.

[3] Of course, there are likely to be network effects associated with public equity markets. If each additional exit from the public market undermines the attractiveness to other investors and companies, there may be a benefit to swift action.

---------------

By Peter Andrews, Senior Adviser at Oxera; Callum Watling, Consultant at Oxera and Peter Hope, Partner at Oxera.

This post is in response to 'A bold governance tonic for UK equity markets’ by Brian Cheffins, S.J. Berwin Professor of Corporate Law at the University of Cambridge.

The ECGI does not, consistent with its constitutional purpose, have a view or opinion. If you wish to respond to this article, you can submit a blog article or 'letter to the editor' by clicking here.