The ECGI blog is kindly supported by

How supply chains undermine sustainable capitalism - and how to fix them

In the spring of 2020, facing massive uncertainty about how the Covid-19 pandemic would affect the health of the economy and demand for new cars, automakers slashed their orders for semi-conductors. In 2021, when the economy roared back to life, those automakers lost an estimated $210 billion in revenue as their inability to secure an adequate supply of suitable semiconductors caused them to scale back production in the face of soaring demand. Automakers were not the only ones hurt. The dearth of new vehicles created additional demand for used vehicles. The 25 percent increase in the price of a typical used car in 2021 was both the highest increase on record and a meaningful contributor to inflation.

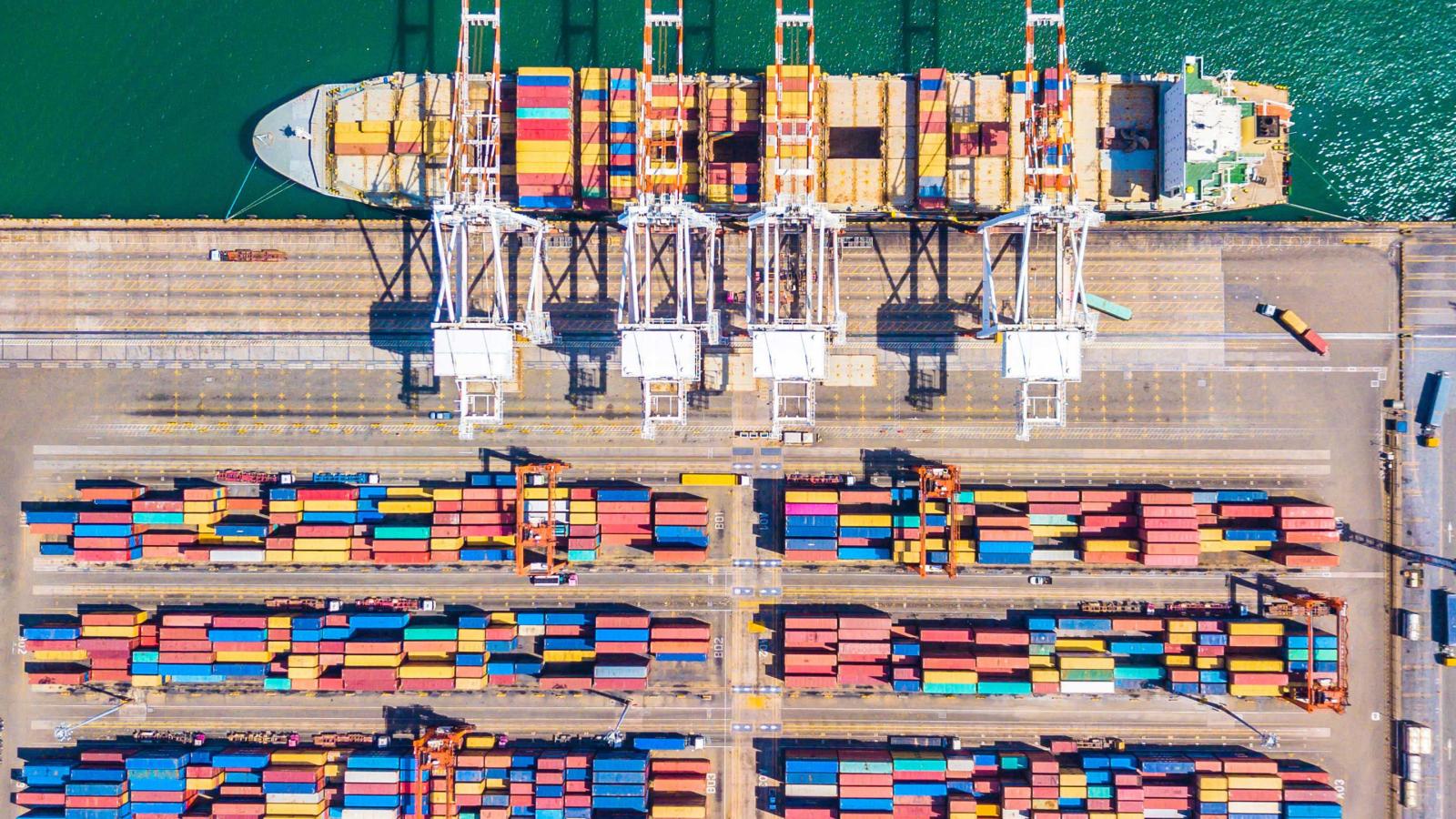

Long supply chains often make it impossible for firms to know the actual impact of their goods on workers and the environment

The decision by automakers to slash expenses in the face of a shock, and thereby deny valuable revenue to a critical supplier, may seem like a classic case of short-termism. In many ways, it is. Yet it was also bad risk management and a reflection of the ways firm leaders have failed to pay adequate heed to the many risks and unknowns that can flow from decisions about what and how to outsource. As I explore in my new book, DIRECT: The Rise of the Middleman and the Power of Going to the Source, the growth of today’s long and complex supply chains has often helped lead to lower prices and seemingly more efficient modes of production. But it has also introduced new sources of fragility—leaving firms both exposed to more risks and less able to see those risks. And the way long supply chains often make it impossible for firms to know the actual impact of their goods on workers and the environment—information that consumers and investors increasingly demand—makes intermediation design all the more central to current efforts to promote sustainability.

As I examine in DIRECT, in sector after sector, from food to finance to retail, supply chains connecting—and separating—have grown in length and complexity for over a century. The advent of steam reduced the costs of moving inputs and goods across countries and around the world. Developments in IT so enhanced communication as to allow production to become a multi-nodal, multi-continent undertaking. The easier it was to overcome the information and logistics challenges that separations create, the more separations that could seemingly be cost-justified. This process of dis-aggregating production so each step in a production process undertook only what it could do most cheaply, played a significant role in lowering prices and, when driven by factors beyond efforts to arbitrage different regulatory regimes, often enhanced efficiency. Yet each separation also created the need for an additional layer of intermediation, leading to ever more intermediaries, transforming firms that had been makers into intermediaries, and creating a far more complex and interconnected system.

Efforts to lower prices by allowing supply chains to grow ever longer meant that a shock anywhere along a chain could have outsized effects

As the supply chain breakdowns of the past year make clear, this transformation also introduced new vulnerabilities and created new types of fragility. The pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine revealed that efforts to lower prices by allowing supply chains to grow ever longer meant that a shock anywhere along a chain could have outsized effects. Accentuating the challenge, the opacity bred by long chains and the complex ecosystem that they constitute meant that in the face of shocks, firms often neither knew nor could readily learn how a particular shock would impact the many different supply chains on which it had often come to acquire. This added uncertainty often led to even more outsized reactions and effects, as embodied in the now oft-discussed “bullwhip effect.”

As the automaker example makes clear, however, it is not just the length of a chain but the nature of the relationships along it that matter—for individual firms and the broader economy. It is the combination of a complex, highly interconnected system with atomistic behavior which helps explain why the supply chain problems the Federal Reserve kept insisting would be “transitory,” have been anything but—much to the chagrin of firms and central bankers around the world.

Alongside hiding exposures, length and complexity of chains can also hide a lot of bad behavior

Yet the loss of resilience is not the only adverse consequence of the many layers of separation common to intermediation schemes today. Alongside hiding exposures, length and complexity of chains can also hide a lot of bad behavior. So long as the only aim is to maximize production relative to inputs, this information loss may not seem like a big deal. But once consumers want to know something about the way a good’s production affects workers and the planet, the costs of this opacity go up significantly. Certification schemes, such as FairTrade and organic, can help to close some of this gap, but the research suggests that these schemes often fail to deliver the promised benefits, and real accountability can be nearly impossible when the costs of tracing far outweigh the actual value of a good.

There are no easy answers to the tradeoffs at play in decisions about when and how to outsource. Intermediaries play critical roles in today’s economy, and there’s no going back to a world without them. Too often, however, firms have paid too much heed to the short-term cost savings that greater dis-aggregation can help unlock, and too little to the attendant risks and information loss. For firms and policy makers seeking to promote the accountability and resilience that true sustainability demands, re-examining intermediation design through a far more critical lens can make it easier to identify areas where the tradeoffs may not be justified. And shortening existing chains or seeking to build new, shorter chains designed to prioritize resilience and transparency can go a long way in helping firms achieve their sustainability aims.

--------------------------------------------------------------

Kathryn Judge is the Harvey J. Goldschmid Professor of Law at Columbia Law School, ECGI Research Member and the author of DIRECT: The Rise of the Middleman Economy and the Power of Going to the Source (Harper Business, 2022).

This article reflects solely the views and opinions of the authors. The ECGI does not, consistent with its constitutional purpose, have a view or opinion. If you wish to respond to this article, you can submit a blog article or 'letter to the editor' by clicking here.